By Ieuan Jones @_Ieuman

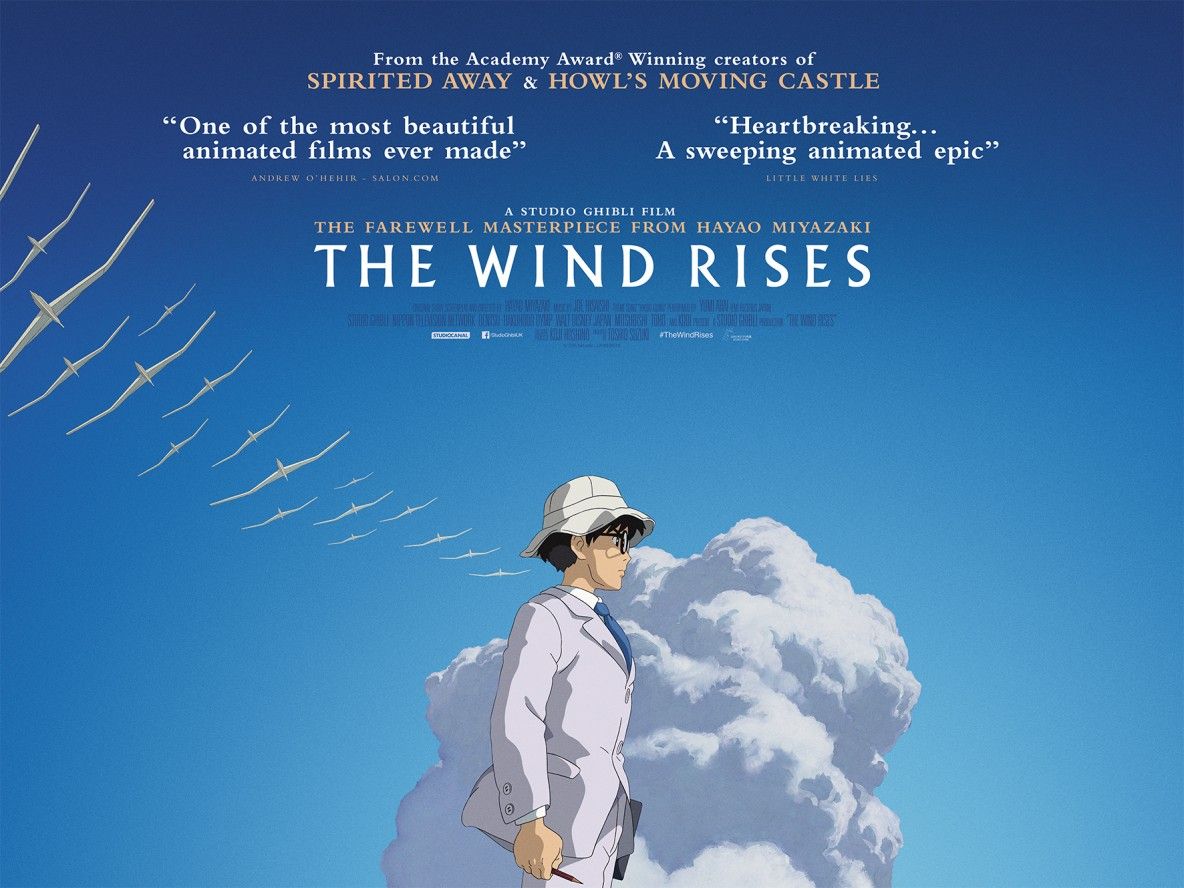

Watch The Wind Rises at Plymouth Arts Centre 12 – 14 July 2014.

Last September, Hayao Miyazaki, founder of the Japanese animation production company Studio Ghibli, announced that his latest film, The Wind Rises (2013), would be his last. Although he has threatened retirement before, at the age of 73 and willing to hand over the reins to a younger generation, it does seem like he means it this time. Taking him at his word, then, The Wind Rises is a fittingly dazzling and compelling end to his custody over one of the most extraordinary series of works in modern cinema.

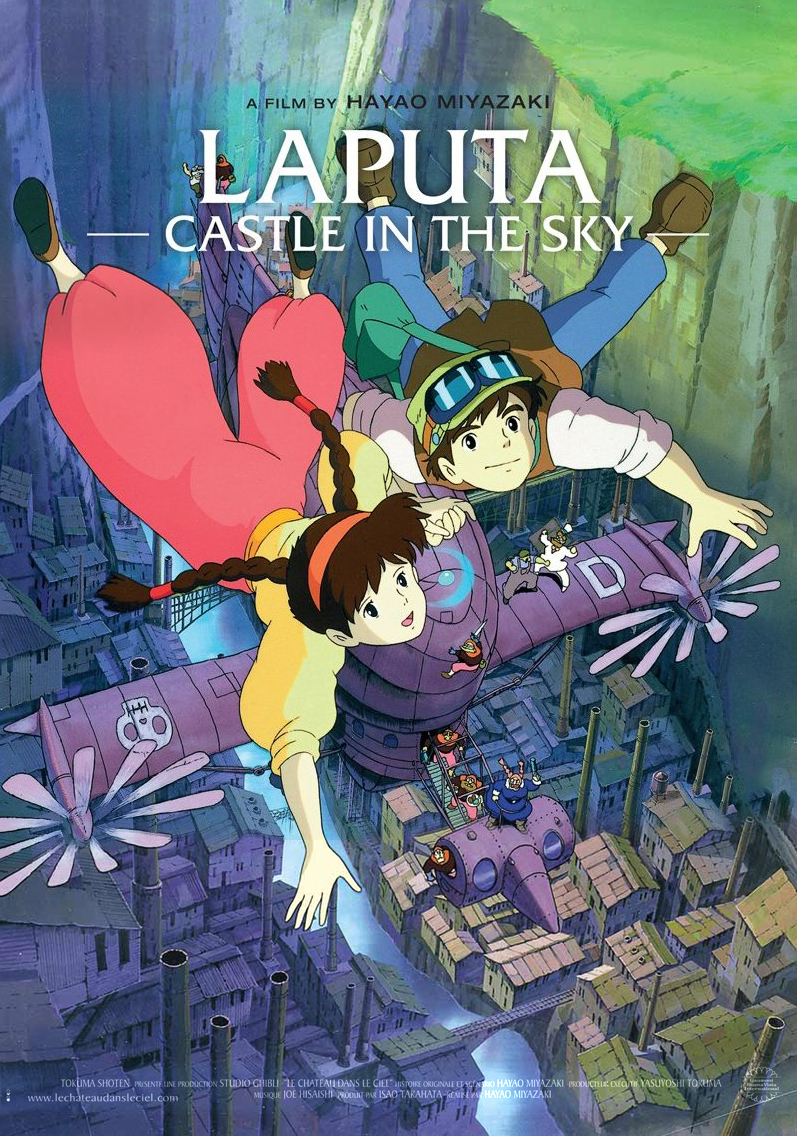

His first feature for the studio, Castle in the Sky (1986) contains much of the DNA that would find its way into the studio’s later releases. An orchestra of pirates ships sailing through the clouds, secret princesses and gigantic robots tending to ruined gardens, the film also seemed like more than the sum of its parts. Behind the astonishing visions it felt like something altogether more interesting was being said. Themes such as the needless destruction of war, the responsibilities of science and the law of unintended consequences all teemed beneath the eye catching veneer. Disney this most certainly wasn’t. And this was just the beginning.

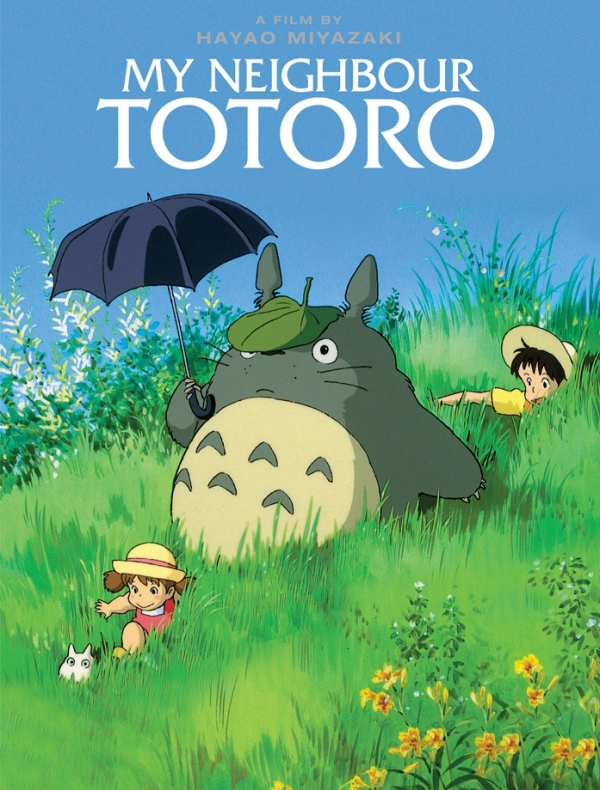

My Neighbour Totoro (1988) has long since passed into fan folklore – just about the most loveable of modern animated characters (not a spirit, as Miyazaki insists), the title hero is a kindly creature who befriends two small children in late 50s Japan. The film is full of fantastical images, including house spirits and, of course, the Catbus (a particular favourite of mine). Yet, again, there is more going on beneath the surface. The main characters, Satsuki and Mei, spend the film dealing with the long term illness of their mother. The film also touches on an ecological message, a theme that would become much more powerful in later works. As for Totoro himself, he became Studio Ghibli’s emblem, perfectly encapsulating the company’s own magic and charm.

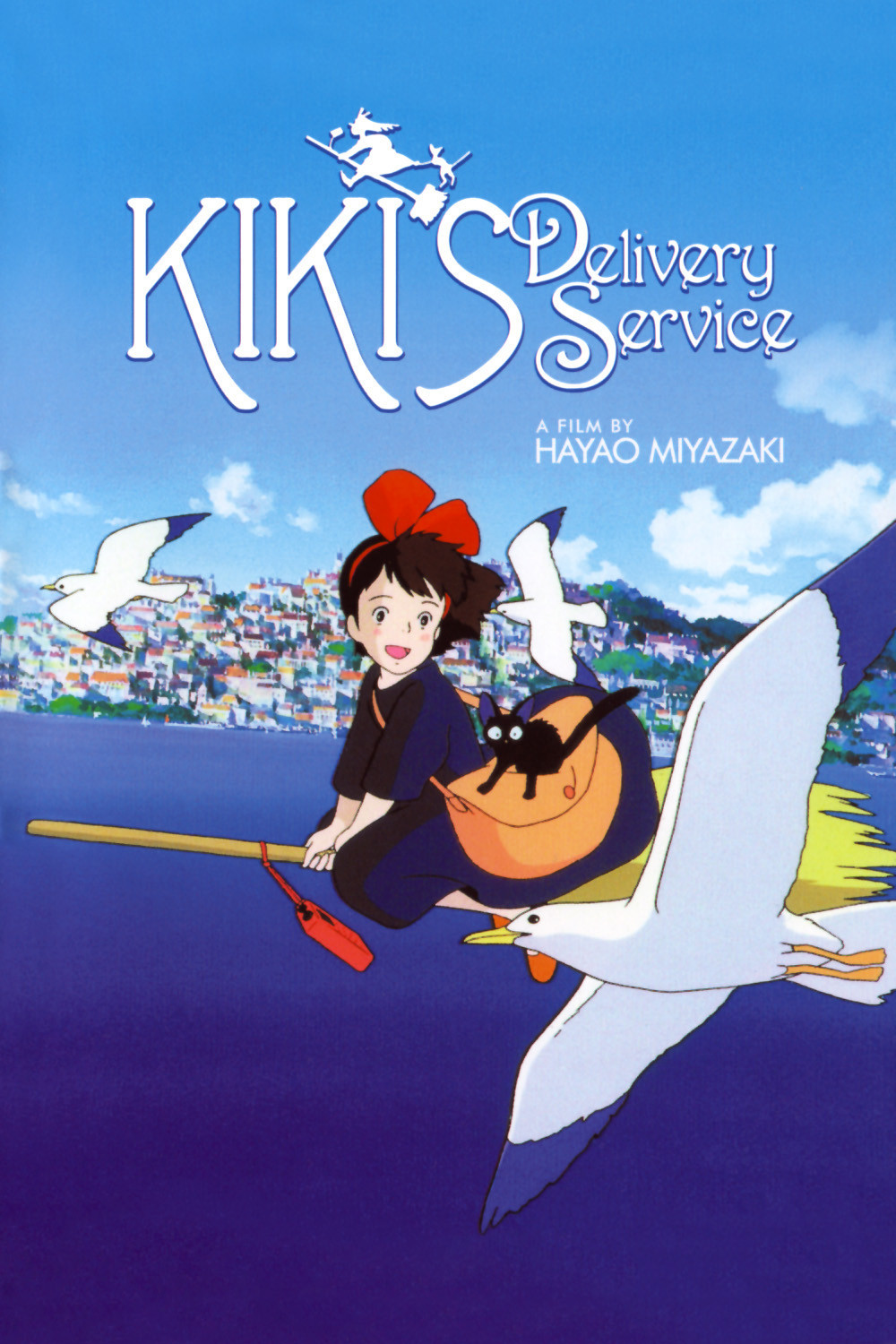

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) was another hit and a heap of fun, featuring more flight, more animal spirits – and even a cameo from our friend Totoro. However, proving that the studio was not a one man show, Grave of the Fireflies (1988) was a powerful tale of struggle and survival in the darkness of Second World War Japan. Coming this time from the hand of Isao Takahata, many consider this to be one of the great modern anti-war parables.

Miyazaki entered the next decade with Porco Rosso (1992), which made his obsession with early aviation explicit, and carried yet more messages of tolerance and pacifism (“I’d much rather be a pig than a fascist”). However, it was his next feature that proved to be the studio’s first real landmark.

Princess Mononoke (1997) truly was a quantum leap in both quality and achievement. The themes he had been developing since the beginning, including the relationship between man and his surroundings, and the responsibility that comes with technological advances, all blend into one of the most startling and thought provoking films ever made. Set in a fantasy medieval Japan, the humans are at war again, with themselves, with other animals, with the entire idea of nature. It’s an environmental parable, yes, but this is not any old plea for more recycling and less bypasses. Take Lady Eboshi, ruler of Irontown, who could so easily have been portrayed as another cold hearted villain, consciously wiping out nature for its own sake. Instead, she is shown as someone with a strong benevolent streak to match her ruthless self-interest. Her blindness to the destruction she wreaks is a powerful metaphor for rapacious capitalism. And who can forget those visions – from a stag-headed god who towers above the forest, to the thousands of tiny kodama tree spirits that inhabit it. Understanding the provenance of undertaking such a feat of animation, Miyazaki personally oversaw the drawing of 144,000 cells for the film, and even helped redraw 80,000 himself. His efforts were not in vain. This solid gold masterpiece was also a solid gold hit, grossing over 14 billion yen in his native Japan (beating Titanic) and plenty more overseas.

After that accomplishment, no-one would have blamed Miyazaki for calling it a day. Instead, he went on to deliver a film that could even give Mononoke a run for its money. Spirited Away (2001) was a proper hit this time on an international scale. People fell in love with its strong female lead (another theme running consistently throughout Ghibli’s history) and alternate universe of masked spirits, ghost trains and gigantic babies. Family, another recurring theme, was as prominent here as it was in Totoro. It charmed even the Academy, who gave it the Oscar for best animated feature. Miyazaki, however, did not turn up to collect his statuette, deciding to use it as an opportunity to protest the invasion of Iraq. This man truly did walk it like he talked it.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) contained more bewitching flights of imagination, but felt somehow darker than previous efforts. Profoundly influenced by the invasion of Iraq, the continuous threat of war and the mechanics of destruction seep into even its lightest moments. The title character, as well as seeming to be cold and dispassionate is in fact deeply conflicted over his pacifism, as he also possesses within him the power to prevent more killing and bloodshed. One of Miyazaki’s most ambiguous characters, Howl finally does what he feels is right when he finds something worth protecting, the love of his life.

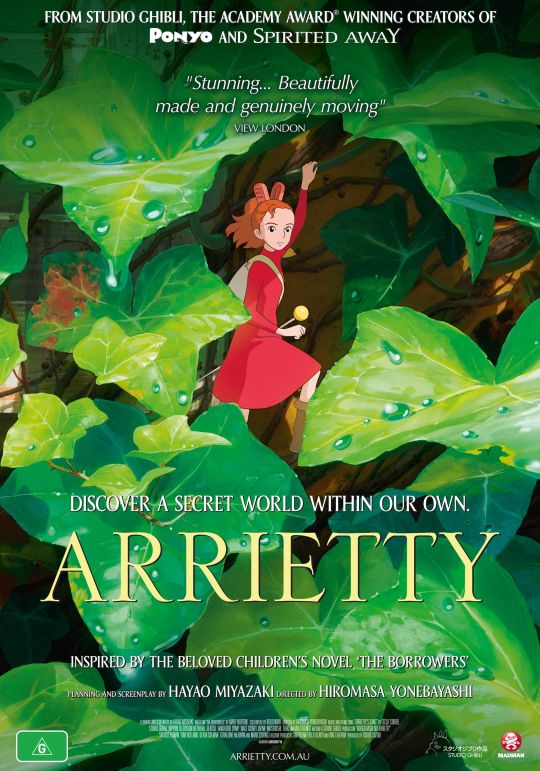

There then followed a period of semi-retirement for Miyazaki, popping up briefly to oversee the captivating children’s adventure Ponyo (2008), although the studio continued to put out interesting work. Tales from Earthsea (2006), another fantasy with undertones of war, was this time overseen by Miyazaki’s son Gorō. Meanwhile, the exquisite Arietty (2010), was based on the children’s classic The Borrowers.

And now, at last, the great man’s swansong. The Wind Rises deserves to stand among the very best of Miyazaki’s work, so rich it is with striking images and enigmatic characters. It is perhaps his most complex and intriguing film. It is a biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, chief engineer and designer of Japanese aircraft in the build-up to the Second World War. Typically, he is a conflicted character. He is obsessed, like Miyazaki, with flying, but he also knows that the planes he will design will be used for untold destruction. Again typically, he is told in a dream that he must follow his path, whatever the consequences. Jiro is an idealist whose dreams are colourful and full of flight, but the world he inhabits is dark, cynical and dangerous. It is full of poverty and its consequences, and the hidden violence of shadowy agencies.

Wind pervades the film, from the soaring kind that keeps his planes airborne, to the gales that spread the flames over Honshu in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake in 1923. It is fitting here that wind and flight should be seen as such powerful forces: “Ghibli” is named after an Italian WWII aircraft, and is itself a rough translation of “Mediterranean wind”. (The translation of “kamikaze”, incidentally, is “divine wind”, and in a key moment one of Jiro’s planes can be seen practicing dive bombing techniques.)

Ultimately, Jiro follows his dream yet is able to reconcile his decision with the one thing that manages to make his life worth living, the love of his wife, Naoko. However, Naoko herself is afflicted with disease, first tuberculosis and then a related lung infection that puts her at arm’s reach in a sanatorium. A gust of wind brings them together unexpectedly when he captures her floating parasol, and it is the wind again that signifies to Jiro that her life can be taken away just as easily. One of the film’s messages appears to be that we should hold onto the things that matter in this life while we have the chance, as everything is fleeting.

His final work, like the rest of his remarkable canon, depends on the power of dreams, although not in any conventional way. Miyazaki more than anyone appreciates that dreams, like childhood, as well as being landscapes of imagination and discovery, can also contain a perilous darkness.

Comments

No comment yet.