Anyone who visits the cinema regularly will know that finding a film that stays with you, long after the credits have rolled, is an increasingly rare experience. In Jonathan Glazer’s Holocaust drama The Zone of Interest, the mark left on the audience is indelible.

Loosely based on the Martin Amis novel, The Zone of Interest details the life of Commandant Rudolf Hoss, who oversees the running of the Auschwitz concentration camp. In a series of astonishing reveals, we learn that his spacious family home backs directly onto the camp itself; only a wall divides them. Rudolf (played by Christian Friedel) and his wife Hedwig (a superb Sandra Huller) enjoy a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle built on the suffering of those caught up in the Holocaust. As Rudolf heads off for work, going about the business of genocide, Hedwig lazes about while an army of servants tend the house and gardens. These servants have narrowly avoided the camp, for now, but are still living in fear. The house is scrupulously clean and tidy; and the family feast on delicious, ample servings of food. Rudolf and Hedwig experience a level of luxury unthinkable in wartime, but it is all purloined. Hedwig, along with other Nazi wives, bids for stolen Jewish-owned items at auction; they dish out amongst themselves the best jewellery and clothes. Glazer wants to show us the “banality of evil” and it is perfectly captured in the scenes where Hedwig swans about in a mink coat that has been taken from someone who has just arrived at the camp: admiring herself in the mirror, she fishes out a half-finished lipstick from the pocket and decides she’ll keep that too. When her friends visit, she boasts about how the officers found a diamond hidden in a tube of toothpaste. In a truly nauseating moment, she gloatingly refers to herself as “the Queen of Auschwitz”.

Rudolf Hoss, considering he is the driving force of the Hoss family fortunes, is surprisingly unimpressive. Approaching middle age, he is a mid-level bureaucrat. whose unquestioning amenity makes him a plum choice for promotion. While older officers might dither, Hoss’ “energy” is what gets him noticed. Friedel and Huller don’t play their villains larger than life, but really dig into the ordinariness of the couple. As repellent as they are, Glazer is careful to underline how the atrocities carried out in Hitler’s name were taken up by men and women not that different from ourselves. Complicity was rewarded, and the wall that officers like Hoss built in their minds, to allow them to commit such cruelties, would become unassailable. The Zone of Interest is not only an examination of how quickly morality can dissipate, it is also a study of power.

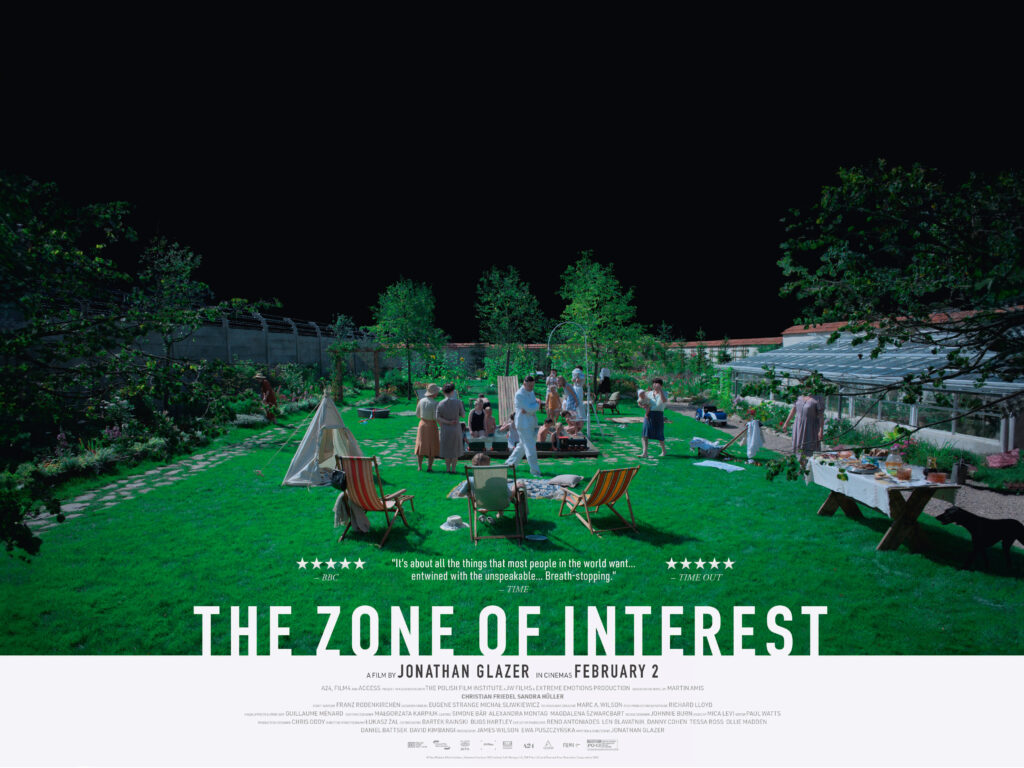

Glazer’s choice to focus on this aspect of the Holocaust makes for extraordinary cinema. The Hoss family go about their lives as if in a dream – utterly detached from what is happening over the wall, as if it is happening elsewhere. They invite their friends around for summer parties; their children dive eagerly into the Hoss swimming pool. Behind them, the Auschwitz furnace churns out thick, black smoke. The sound of gunshots punctuate their dialogue; screams and cries of distress fade into the background as Rudolf and Hedwig sit up in bed and reminisce about their holidays in Italy. The level of emotional disconnect is absolute: they have been living here for three years.

In deciding how to depict the horrors of the camp, Glazer goes not with visuals, but portraying the hopelessness through a soundscape that is both mournful and menacing. The film starts with a blank screen, and an encroaching wall of sound that threatens to overwhelm the senses. Sound designer Johnnie Burn overlays dozens of voices in anguish: Glazer diverts the camera from what is happening but we are not spared the devastation. Fear is depicted in every shade: the cries of prisoners intersect with a trembling teacup, as the servant holding it is callously threatened by Hedwig. The score from composer Mica Levi uses choral elements to create not melody, but a wave of discordant sound, building into a gruelling, pressing urgency. While the restraint applied to this film is remarkable – we don’t see a single person being killed – the use of sound insists that we fill in the detail for ourselves.

Glazer looks for any scrap of humanity in this story, and the subplot of a young girl collecting apples and leaving them near the camp for prisoners to find is a rare moment of hope. But it is the brutality – unthinking and unrelenting – that permeates this film to its core. By circumnavigating the usual observations of life in and around a concentration camp, The Zone of Interest often feels more like a documentary. But where a documentary maker has objectivity, Glazer refuses to shield us or himself.

While this is a period piece, with a profoundly moving coda from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, The Zone of Interest has its gaze fixed squarely on the present. In our reaction to what is an intensely visceral experience, Glazer reassures us. We feel empathy, where Rudolf and Hedwig couldn’t. A film that is nothing short of a masterpiece, Glazer’s achievement is incredible. The Zone of Interest doesn’t just teach us about the past: it warns us not to repeat it.

The Zone of Interest is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema from Friday 23rd – Thursday 29th February.

Reviewed by Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.