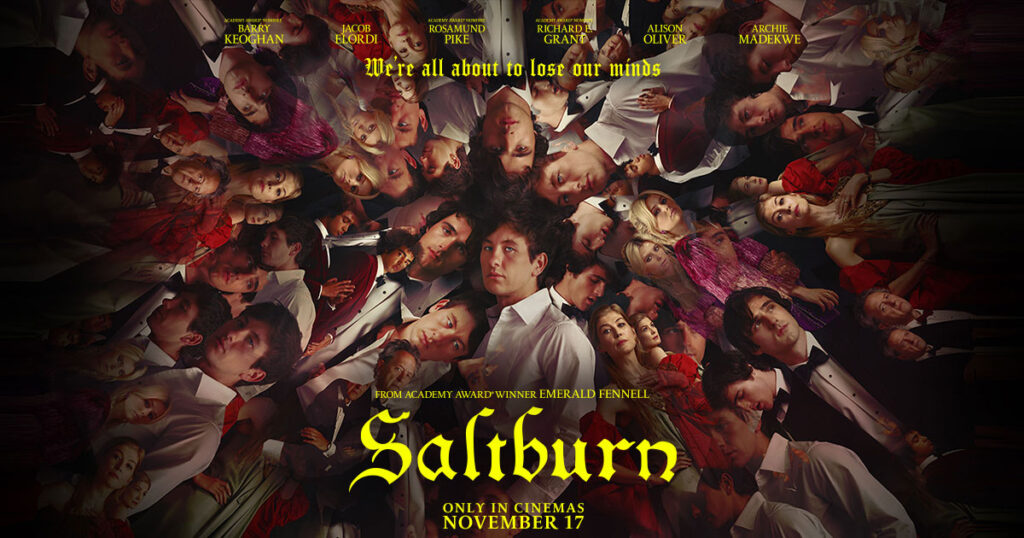

Balanced somewhere between a “gothic love story” and horror, according to its director, Saltburn is a film with serious pedigree.

Loosely based on the family featured in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, this later-generation story begins in 2006, and owes as much to cinematic references as Waugh’s examination of Britain’s class structure: think Kubrick’s chancing hero Barry Lyndon meets The Talented Mr Ripley.

Director Emerald Fennell uses her own experiences to depict life at an Oxford college. A scholarship boy, Oliver Quick (played by Barry Keoghan), arrives at the university, very much a fish out of water. His first introduction to the privileged side of Oxford is when his classmate arrives 20 minutes late for their tutorial. Farleigh Start (an excellent Archie Madekwe) is the cousin of Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), heir to Saltburn.

A chance encounter has put Oliver in Felix’s orbit. As Oliver begins to integrate himself into Felix’s group, the film notes how the air around them is a little headier: the insults are more cutting; the Jagerbombs at the pub, eye-wateringly expensive. Fennell, a graduate of Greyfriars, casts a satirical eye on university life for those who will never need the benefit of a university education. Oliver – so conscientious he ploughs through the entire summer reading list when his tutor hasn’t even read half of it – starts to learn that the set of rules that got him through the college gates simply don’t apply to Felix. Tall, classically handsome but sensitive, Felix takes an interest in Oliver, especially when Oliver reveals his tragic home life. An alcoholic mother, and a drug-addicted father who has recently died (the character’s background darkly mirrors Keoghan’s own), he is invited to spend the summer break at Saltburn.

The scenes at ancient, beautiful Saltburn – Oliver adjusting to life at the manor; gloriously sunny days by the pool with Felix and his sister, Venetia (Alison Oliver) – are overlaid with an indulgent early Noughties soundtrack. Bloc Party, Arcade Fire, Sophie Ellis-Bextor and Girls Aloud drop you into a moment. Pre-Brexit, pre-Covid, surrounded by beautiful artefacts and second-rate Rubens, Fennell really sells us the dream. Coupled with the double-act that is Sir James and Elspeth Catton (Richard E Grant, Rosamund Pike playing the parents, and having the time of their lives), Oliver can easily be forgiven for having his head turned. Held at arms’ length by Farleigh, and the Catton’s butler, Duncan (a superb Paul Rhys), Oliver is welcomed in by the rest of the family. His sexual longing for Felix – a source of tension between the friends – begins to spill over, and (getting a little too comfortable) Oliver finds a more amenable partner in Venetia. Fennell reveals the third act as Elspeth throws Oliver an extravagant birthday party: the gothic tones, in the shade of a blistering summer, now come to the fore. The Dionysian delights start to leave a bitter taste.

With the release of Saltburn, there have been criticisms aimed at Fennell: can someone so immersed in this social class really view it with any disparity? But it is in the attention to detail that Saltburn really comes to life. For example, the breakfast scene, where Oliver has to be told how breakfast works for the upper classes (eggs served separately); and the surprising equation that the bigger the stately home, the smaller the telly. Oliver’s confusion at everyone crowding around a tiny telly in the library is shared by the audience. The social satire is perfectly pitched, because it’s delivered by someone ‘in the club’. As the daughter of jeweller Theo Fennell; born into wealth and privately educated, Emerald shouldn’t excel at the nuanced observation and empathy required for film-making. But the sharp eye, the survival instinct: Fennell aligns herself far more closely with Oliver than Felix or Venetia. Even as the film reaches its darkest phase (and this is a film that does not shy away from controversy), the Cattons find themselves overwhelmed by events; Quick naturally rises to the occasion.

Saltburn merges riotous comedy with acidic, noir satire. The blending of genres largely succeeds, but the resolution – the tying-up of loose ends – feels messy and incoherent. However, it’s not enough of a fault to undo the rest of the film. The performances, across the board, are sensational. Keoghan’s amoral anti-hero pulls us in, and then reviles us. Rosamund Pike as silly but glamorous Elspeth nearly steals the show with her one-liners. Paul Rhys’ watchful butler is far from dispassionate: his range of emotion provides Saltburn with much-needed depth.

While not a perfect film, Saltburn grabs your attention and refuses to let go. Fennell’s portrait of the outsider is just as compelling as her depiction of a class frozen in time. Fennell answers her critics by demonstrating that she is able to see both sides of the coin. It feels like this subject isn’t fully done for her, either. Saltburn initially dazzles, the visuals entice, but the cracks soon appear when everyone stops having fun. There is a better film to be made, once Fennell decides it’s time to revisit.

Saltburn is showing at Plymouth Arts Cinema from Friday 24th – Wednesday 29th November with a Bringing in Baby Screening on Thursday 30 November.

Reviewed by Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.