When, on 5th October, The New York Times published its investigation into accusations of sexual assault by media mogul, Harvey Weinstein, the world finally got a real look behind the curtain of an industry we constantly glamourise. Since then, more than 30 high profile men involved in media production have been accused of sexual misconduct. The near-daily stream of women coming forward to tell their stories of harassment has revealed that this toxic, manipulative behaviour has become endemic to the business. Now the question is: what do we do next?

For years Hollywood, and we, as consumers, have accepted this culture. The Weinstein article revealed that multiple women were paid to keep quiet about his misconduct, and people from every echelon of the cinematic assembly line were complicit in its hush up. More has been done to silence victims than to prevent further abuse of power by the perpetrators.

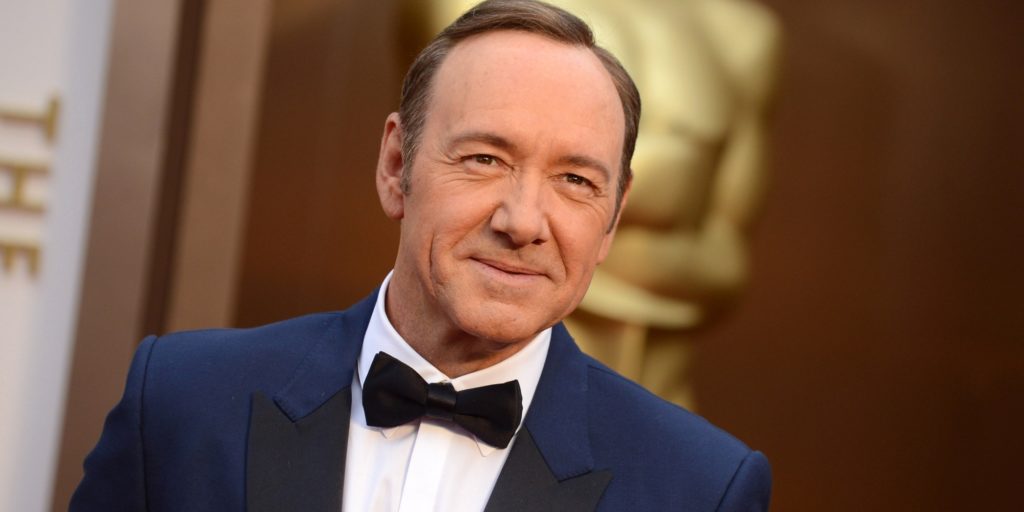

This time, however, the internet is outraged, so Hollywood has been forced to address the issue or risk ostracising its consumers. The repercussions for those exposed since 5th October have been encouraging: Kevin Spacey is being entirely erased from Ridley Scott’s latest movie following allegations of sexual harassment against several adults and a minor; the BBC have shelved its Agatha Christie drama, starring Ed Westwick, until an investigation into the three accusations of sexual assault he faces has been concluded; Harvey Weinstein has been fired from his company and expelled from the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. Almost all those who have faced allegations in the last month have experienced decisive fallout.

But with every new allegation, there is an urgency as interest from social media wanes. How long will this public outrage protect those who are speaking out? At what point will the internet bore of listening, and with them, the Academy start ‘forgetting’? We cannot continue, as we have in the past, to sweep the names of predators under the red carpet and turn a blind eye when they creep out from the other side, unscathed.

Casey Affleck, accused of sexual harassment by two women in 2010, won Best Actor at the 2016 Oscars for his role in ‘Manchester by the Sea’.

Woody Allen, who has been accused of sexual abuse by his adopted daughter, premiered his latest film ‘Wonder Wheel’ at the New York Film Festival on 14th October.

Roman Polanski, pleaded guilty to ‘unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor’ in the 1970’s, yet googling him reveals a quaint little factoid: ‘Did you know: Roman Polanski is the second-oldest winner for the Best Director Academy Award (won for “The Pianist” at age 69 years, 217 days).’

If we want to see sincere change in the industry we need to isolate all of the perpetrators. No one can duck out of justice because they’re handsome, or they make us lots of money, or they’re talented. These people have undoubtedly contributed to our artistic landscape, but at what cost are we willing to let them continue to do so?

The scandal revealed that huge numbers of films that we’ve already immortalised in cinematic history were, in fact, produced on the back of abuse. Do these films need re-appraising in light of events? Boycotting? Is that even possible with misconduct so prevalent in the industry? Comedian Louis C.K. (accused of indecent exposure and masturbating in front of five women), and Woody Allen are both auteur artists; they are intrinsic to their work. In ‘Annie Hall’, sexual coercion is normalised by Allen’s character. Louis C.K.’s latest film ‘I love you, Daddy’ is literally about a pedophiliac film maker. Their actions seep into their black comedy in a way that makes it difficult to disentangle the art from the artist, and their work should be extradited from our cinematic territory because of this. Yet, for most of those accused, what to do with their historical work is a trickier decision to make. While none of these men should be given such power again, their films must be allowed to live on, if only because we cannot let them define work that hundreds of guiltless people also contributed to.

What we can do, however, is use this moment to champion the work of artists that a predominantly white, heterosexual, male Academy has sidelined – women, people of colour, people in the LGBTQ+ community. Let us not neglect this mass of talent any longer. By validating these people as artists of value, we validate their voices as social commentators too. And it is the lack of belief in, and silencing of, the testimonies of women that led the abusers in Hollywood to remain unaccountable for so long.

We can tackle this by promoting initiatives such as the ‘F-Rating’ which advocates greater representation of female-makers in film. The qualification is given to films if they meet the following criteria:

- Directed by a woman and/or

- Written by a woman

- Has significant women on screen

The F-Rating was built on the foundations of ‘The Bechdel test’ which focusses solely on on-screen female presence. The F-Rating, however, commends films for their makers as well as their content. The F-Rating highlights how few films made by women make it to the cinema and aims to encourage film-makers to address gender imbalance throughout the industry. It was first introduced at the Bath Film Festival in 2014, but has since been adopted by cinemas and festivals internationally, including Plymouth Arts Centre, as a sign of solidarity to all those underrepresented in film.

The #OscarsSoWhite campaign that occurred around this time last year, in some ways set a precedent for the #metoo movement in October which has just been named Time Magazine’s Person of the Year. It led the Academy to expand the rules for entrants looking for appraisal. From 2019, films hoping to win BAFTA awards for outstanding British Film and outstanding Debut by a Director, Writer or Producer will have to meet the BFI Diversity Criteria to be considered. These criteria focus on increasing representation of disability, race, gender and sexuality in film.

Whilst we must actively celebrate this move, we also have to be our most critical selves to ensure that the effort is sincere. Deconstructing these environments of power-manipulation and silence in Hollywood will require an assiduous effort, and whether that environment has harboured institutionalised racism or sexual misconduct, we have to be attentive, even when the hashtag stops trending.

It is our responsibility, as consumers of media, as much as it is Hollywood’s, to send a message of intolerance. It may be inconvenient, it may disrupt your christmas telly schedule and it may ruin your opinion of your favourite actor, but ultimately, your temporary entertainment should not be the priority. Securing these events in our collective memory is a necessary step towards eradicating the culture that normalises them, and if we want to save the art form that we love, we must not waver in our outrage at those who have sullied it.

Written by contributor Eve Jones

Comments

Comments are closed.