Helen Tope has written a review of The Birth Of A Nation, which is showing in our cinema from 27 January – 2 February. Tickets available here (all full price tickets for this film are 2 for 1, whether you book online, by phone or at the box office. That’s just £9 for a trip to the cinema for two people!)

The Birth of a Nation tells the true story of a slave rebellion that took place in Virginia, August 1831. The rebellion was led by Nat Turner, a slave-turned-preacher. The group of rebels killed an estimated 65 people during the uprising, ending in a bloody defeat at Belmont Plantation. Having survived Belmont, Nat Turner was executed a few days later.

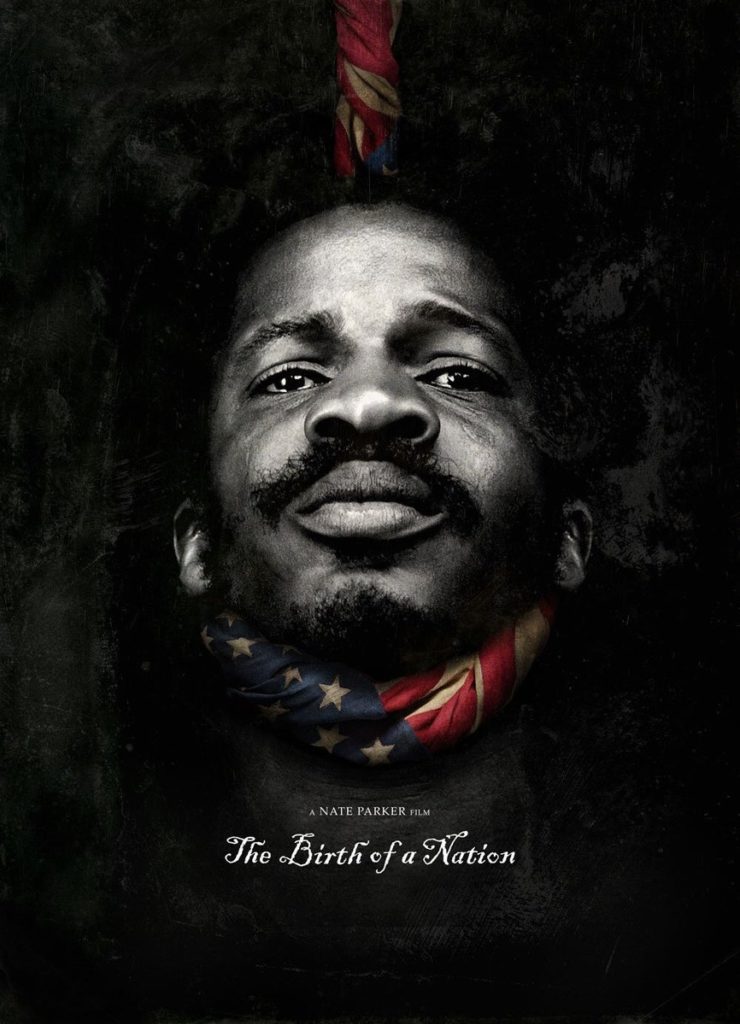

The film; written, directed and starring Nate Parker, deliberately takes its name from the same-titled D.W Griffith 1915 classic. Griffith’s film holds a notorious place in cinema history; with Griffith painting the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force for good. Despite its bold approach to film-making, the subject matter (even at the time of its release) made Griffith’s film difficult for audiences to stomach. Depicting African-American men as “brutish, lazy, morally degenerate and dangerous”, Griffith’s film has become a by-word for controversy. What Nate Parker does, and to some extent, achieves, is to present us with an alternative ‘birth of a nation’. Parker’s film, unlike Griffith’s narrative assurity, gives us instead a history that is anything but certain.

Nat Turner is born into the slave trade, working on the Turner family plantation in Virginia. As a young boy, he displays an interest in books and reading. The Turners, priding themselves on being more progressive than their neighbours, take Nat out of the cotton fields, and into the library. Nat eagerly reaches out for a book, but Elizabeth Turner (an excellent Penelope Ann Miller) chastises him. Those books – novels, biography, history – are not for him. Nat is handed The Bible and together, he and Elizabeth begin to read.

Nat’s development is cruelly impeded, when the local priest dies. Among his last words, a declaration that Nat’s place is not in the pulpit – he is returned to the fields to work. This wound drives deep for Nat, whose resentment and anger builds, as he is later employed as a preacher to spread the good word to local plantation slaves. He is there to placate their disquiet, to preach obedience and supplication. What he finds is a landscape where virtue and morality are utterly abandoned. Slave-owners proudly display their ‘stock’ to Nat and his master, Samuel Turner (Armie Hammer). What they find is degradation, disease and abuse of the most shocking nature. This is a film that believes in show, not tell, and the pristine fronts of the Southern mansions hide a truth that is far grubbier than their well-mannered exterior would suggest.

Nat and Samuel’s once-cordial relationship disintegrates as Samuel’s money worries drive him to drink and Nat, having witnessed horrific abuse of his people, becomes convinced that gentle persuasion is not the path to freedom, but cold, calculated resistance.

The film boasts a complexity not normally seen in big-budget movies, tackling the issue of race. Not all the bad guys are bad through and through; a pin-prick of conscience is often seen in Samuel Turner. By the same token, the actions of the uprising are left without comment, Parker’s intention is that the audience makes up its own mind. The film never editorialises, and it’s a strategy that works well. The Birth of a Nation makes the case that history never reaches an end point; it continues being made and being revised. The last word does not exist. The film ends by disappearing into its own vanishing point – a boy stood in the crowd who witnesses Nat’s execution, is seen in the final frames as a soldier, fighting in the Civil War. He begins what will be (at best) a convoluted journey from slavery, to freedom, all the way to the White House. The Birth of a Nation makes it clear that it does not see Nat’s failed rebellion as a failure in itself. Crucially, it starts to tip the balance, and that is a profound achievement for a way of life where one party had everything to lose, and the other, all to gain. Historians have asked if the abolition of slavery was hindered by Turner’s rebellion, but where Turner succeeded was in stopping the normalisation of the practice of slavery. It reminded everyone that slavery was a construct – and on borrowed time.

A film of such ambition needs a strong cast, and The Birth of a Nation boasts only strong performances from its two male leads, but powerful and persuasive supporting work from Esther Scott (Bridget) and Aja Naomi King (Cherry). Playing Nat’s grandmother and wife respectively, the female characters actively drive the narrative forward at key moments throughout the film. The ambiguity of the relationship between Elizabeth Turner and Nat is particularly well-drawn. Her desire to see Nat become literate and knowing is cut short by the need to maintain propriety. It is a different kind of bondage, but Parker deals with it in a frank and open manner. Even in this deeply unbalanced relationship, there are caveats.

The violence in the film – and as you might expect, there is a lot of it – is brutal, unflinching and uncompromising. The average life expectancy of a slave was just 22 years, and life, such as it was, was lived on a knife edge. Parker very cleverly brings us up to date in a scene where Nat is found walking in the woods and is challenged by the local sheriff. Where is he going? Who does he belong to? Where are his identification papers? This is the one scene that feels utterly modern: a black man, being confronted by authority, is choosing his words carefully, how and when to make eye contact, striking the right tone between respect and deference. This scene is taken straight from 21st century life – for all our strides forward, says Parker, we have made remarkably little progress. Be careful, be brief – it is a lesson still passed down to African-American schoolchildren today.

The film ends, not with triumph, or hope, but with a question. How far have we really come? With recent shifts in the American political landscape, this question matters more and more.

History is not a straight line, and The Birth of a Nation, in is its attempt to bring us to a cyclical view of events, feels very much of the moment. The precarious nature of liberty is at the heart of the film, and it’s a message that speaks to us all. The film’s master-stroke is not to find the segregation, but to locate the universality in the struggle for recognition. The notion of freedom at any price is continually questioned throughout the film, and the conclusion is laid bare: nothing should be taken for granted. Progress is not inevitable. It is hard-won and fought for. It is a message not designed to comfort, but that is entirely the point. A battle has been won, but the war continues. It’s up to us to decide which side we are on.

Helen Tope is a freelance blogger working and living in Plymouth.

@scholar1977

Comments

Comments are closed.