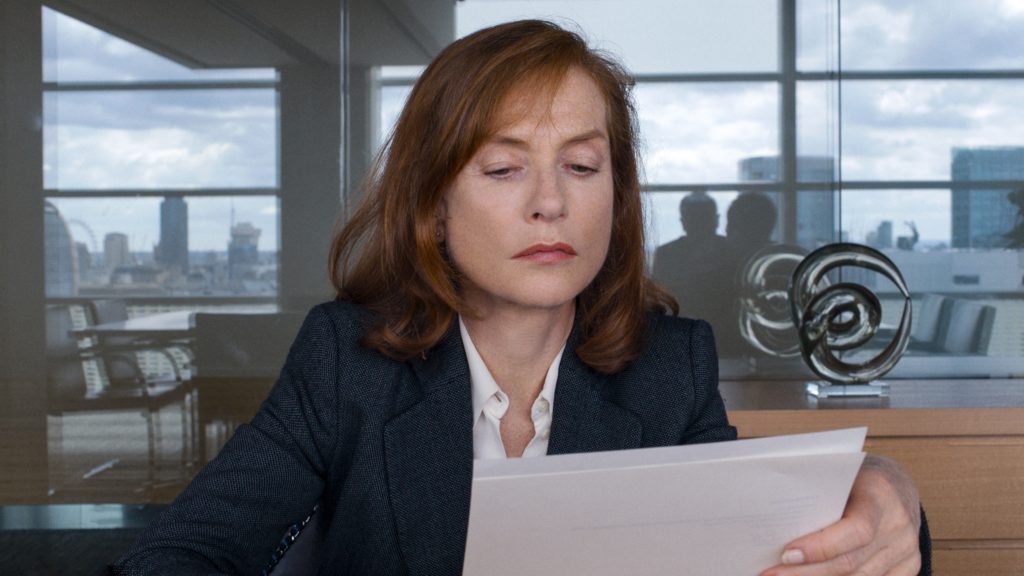

Contributor Eve Jones reviews Happy End from director Michael Haneke, showing in the PAC cinema until Thursday 25 January – limited tickets remaining.

Warning: contains narrative spoilers

Michael Haneke delivers a mystifying and bitter depiction of bourgeois nihilism that will make you laugh because you don’t really know how else to react.

We’re introduced to the film through the phone camera of 12-year old Eve (Fantine Harduin) after she has poisoned her mother with an anti-depressant overdose – arguably the scene which satirises the title most scaldingly. Eve’s darkly funny, indifferent live message feed is the only percussion as her mother slips into a coma from which she will not recover.

Eve is then sent to live with her estranged and emotionally inert father, Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz) and extended family who take little interest in her, leaving Eve’s culpability to be considered only, if ever, with a look over the shoulder in a somewhat cyclical denouement. There is no real protagonist, every character blindly acting for their own ends, only to be surprised when they’re smacked in the face (literally and metaphorically) by the consequences, which Haneke voyeuristically documents with lingering shots.

This self-absorption of all the characters is addressed with distaste throughout the 107 minutes, both via on-screen technology and through Haneke’s auteur lens. The camera mourns for the intimacy that most of the characters lack by viewing them indirectly and often with inaudible dialogue. We watch through glass doors as Jean-Louis Trintignant’s lassitudinous Grandfather, Georges, returns home from a suicide attempt; Eve’s visit to her mother is surveyed from across the hospital room; a fist-fight plays out at a clinical distance.

Another stand-out scene lampoons middle-class preoccupations as we follow Eve through Georges birthday party. Shot at her head-height, most of the strangers she passes are faceless as they drawl their trivial anxieties. The party is then interrupted by the disillusioned Pierre Laurent (Franz Rogowski) thanking the family’s “Moroccan slave” for her evening’s work, just as an equally white-washed party is later disrupted by the arrival of guests straight from the Calais jungle. The discomfort of the party-goers is evident, as is Haneke’s criticism of bourgeois narcissism as he directly contrasts the lavish soirees with genuine hardship. Similarly, Georges quest for death is juxtaposed by the migrant’s will to survive, though his story is told more empathetically, with humour, by Haneke.

Technology also plays a key role in relating the ensemble’s inability to accept their responsibilities. Many major plot points are revealed detachedly through cameras and social media – a near-fatal accident at the family-owned construction site, Thomas’ infidelity and the initial overdose of Eve’s mother. There is a dichotomy between the honesty of the characters’ online interactions and their real-life awkwardness, which is emphasised in every scene by the lack of film score, like a breath held for an uncomfortably long time.

Other reviewers have hailed this as a ‘best of’ Haneke with many references to his previous work and the impeccably lit cinematography of Christian Berger. The actors are puppets in his vision and obediently do not bring vibrancy to their roles, instead cumulatively simmering in his naturalistic indulgence. Haneke starves the audience of many things: music, intimate familial relationships, tenderness, but he also precisely peppers the soap opera with black humour and merciless long-shots. Ultimately, you’re left with a film that serves to both unsettle and entrance its spectators.

Eve Jones

Comments

Comments are closed.