Helen Tope reviews Bohemian Rhapsody, showing at Plymouth Arts Centre until this Thursday (limited tickets available here).

On 13 July 1985, rock band Queen took to the stage at Wembley Stadium. Taking part in Live Aid, a benefit concert spearheaded by Bob Geldof, each act was allowed twenty minutes to perform. Everyone used the same set, lights and sound – the only difference would be the music. Freddie Mercury walked out on stage, sat down at the piano and began to play Bohemian Rhapsody.

Their 20-minute show has become a marker in the history of rock performance, a feat made all the more incredible for the fact that Queen nearly didn’t appear on Live Aid. Bohemian Rhapsody tells the story of how a band became a legend.

Directed by Bryan Singer (X-Men, The Usual Suspects), Bohemian Rhapsody is a nose-to-tail biopic, focusing on the life and career of Freddie Mercury. Born Farrokh Bulsara, Mercury is a born self-styler. Creating his image from the ground up, Mercury is an intriguing mix of flamboyance and shyness; extravagance and creative discipline. On meeting the other members of the band, Mercury designs the band’s name and logo, and begins to steer them towards a new, untried sound.

Living with girlfriend Mary Austin, Mercury is a man of contradictions. Clearly gay, but genuinely in love with Mary, Freddie tries to reconcile his desires, without success. His career with Queen, however, goes from strength to strength. Ditching a lucrative deal with EMI, they plug their single Bohemian Rhapsody through Mercury’s contacts. The response is lukewarm at first, but the song connects with the public and it rockets to No.1.

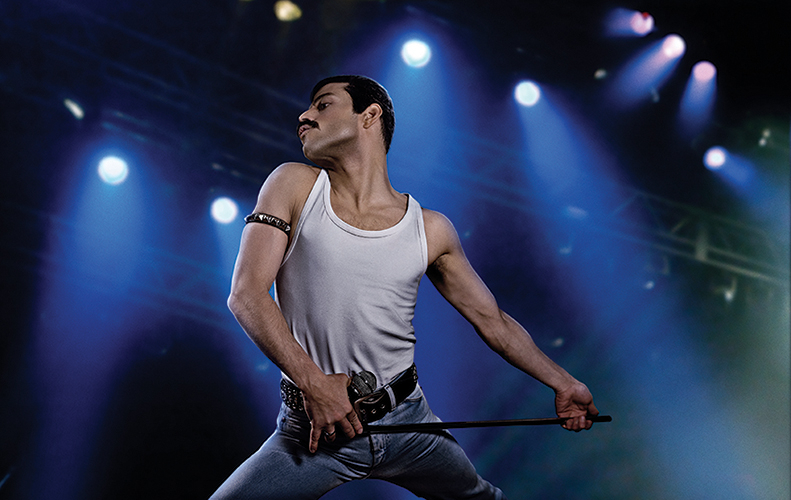

Inhabiting the role from the inside out, Rami Malek delivers a Freddie Mercury that is instantly recognisable. Moving beyond the iconic image, Malek hits moments of light and shade, giving us a performer of conviction and confidence, but a man at odds with his sexuality. It made Mercury highly vulnerable, and his relationship with manager Paul Prenter (a suitably villainous Allen Leech) is catastrophic. He is steered into a solo career, and sedated with booze and drugs. It isn’t until an encounter with Mary Austin, that a desperate Mercury realises that everything must change.

Recreating a band full of characters is no easy task. The temptation to match Mercury’s depth of personality is avoided by Singer, who gives Malek centre stage. There are good performances here – Tom Hollander as the band’s manager, Jim Beach; Gwilym Lee as Brian May – but they are eclipsed by Malek at every turn. Because Malek turns it up to 11, the other performances are dulled by comparison – not because they are less, but because Malek is more.

Under-served by a perfunctory script, Malek chooses to articulate Mercury through performance. ‘Freddie Mercury’ was a performance cultivated over a lifetime; the obvious influences are here – Madame Butterfly and Marlene Dietrich – but Malek smartly uses Mercury’s awkwardness to add a layer of nervous energy that drives everything forward.

The effect is contagious, giving the music its jolting, electrifying quality. Singer’s decision to let the Live Aid concert play out in real time saves the film. In an event watched by a global audience of 2 billion, Queen managed to find the intimacy among the scale. By playing songs the audience could participate in, Mercury, May, Deacon and Taylor reached their audience on a personal level. This performance is always cited as an example of grand gesture, but when Freddie plays the opening bars of Bohemian Rhapsody, he is playing to the individual, not the crowd. His struggle with loneliness (well-documented in this film) made him a more intuitive performer than he is sometimes given credit for. The audience reacts to Freddie’s moments of operatic grandeur, but the quiet, intimate spaces within the performance are why they love him.

As a biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody doesn’t break any new ground. The exploration of Mercury’s sexuality is kept surprisingly PG. We have all the highlights of Queen’s career, but the film doesn’t offer a fresh perspective. Singer’s Queen is fabulous, but it lacks ambition. As a narrative, Bohemian Rhapsody fails. But as a musical celebration, it absolutely soars.

A self-proclaimed group of misfits, Queen are the band that has continually defied the odds. Walking away from EMI; pinning their hopes of a No.1 on a 6-minute operatic riff – they have never done the expected. Their hit, ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, was savaged by critics on its release in 1975. The public thought otherwise, made it a hit and then a classic.

Bohemian Rhapsody, in terms of critical debate, is practically bulletproof. The film is not a game-changing biopic of Mercury – that has still to be made – but the popularity of Bohemian Rhapsody points to Queen’s ability to sidestep the industry, and give the public what they want. The charisma of Mercury’s voice, still vivid and extraordinary after all these years, pulls you in right from the start, and refuses to let go.

The critics were wrong in 1975, and to a lesser extent, have got it wrong again in 2018. Bohemian Rhapsody is not perfect, but that is perhaps the point to be made. Queen is not about perfection, but the life that happens beneath it. Rage, passion, victory – Queen play big with their emotions, and to take a magnifying glass to them is to miss the beauty. The glory of ‘We Are the Champions’ cannot be pinned down by one person, because it is an anthem that belongs to us all.

It is not elegant or refined, but in the final act, as Freddie struts into Wembley Stadium, Bohemian Rhapsody is unmitigated, unapologetic fun. Singer brilliantly captures the pulse of that day – bands coming together to create history, without the self-congratulatory tone that accompanies charity events today. Live Aid belongs to a different era, but Queen’s performance has never lost its shine.

The story of Queen is filled with the possibility of near-misses – if they had bowed to EMI’s demand to shelve Bohemian Rhapsody, would we be talking about them today? Queen’s story was governed by their ability to see beyond trends and predictions, and head in completely the opposite direction.

This film does exactly the same. A complex, psychological portrait it is not. Bohemian Rhapsody skates on the surface, but if you are prepared to forgive, then the film repays you. Music that pulsates with life, performances that have no equal. Bohemian Rhapsody asks us just one question. When given all of this, why would you want more?

Helen Tope

Comments

Comments are closed.