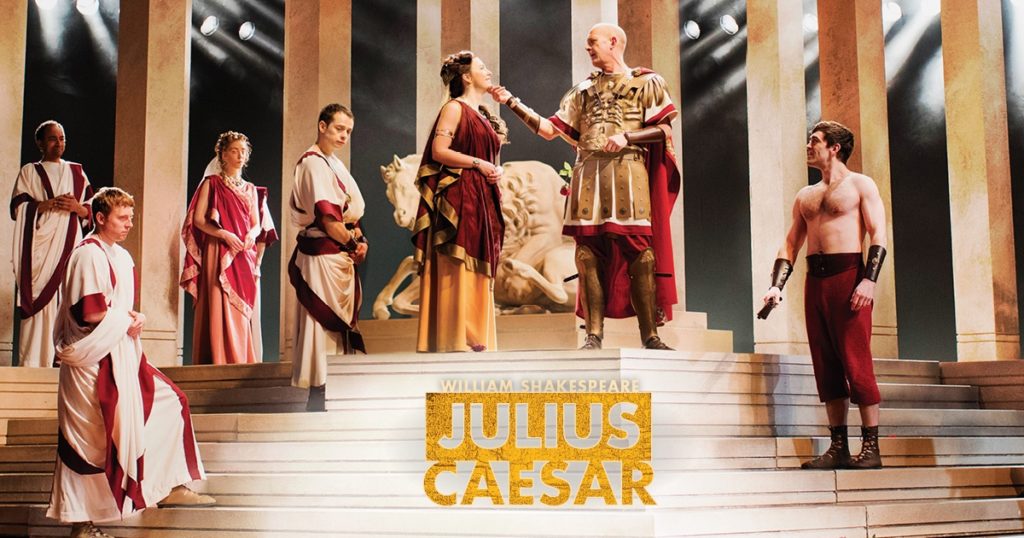

Regular contributor Helen Tope has reviewed the RSC Live Theatre screening of Julius Caesar. Our next live theatre event is National Theatre Live: Obsession starring Jude Law. Tickets are available to book now.

With a story so well-known, in Julius Caesar, it’s not what you say, but how you say it. Winning hearts is what counts in Caesar’s Rome, and if you’ve the stomach to kill a dictator, you better be able to express an idea with more capacity than can be squeezed into 140 characters.

In a live broadcast from Stratford-upon-Avon, this power-play thrills not in the telling of the story, but in how it’s told (no spoiler alerts necessary here). Julius Caesar, with its great speeches, is a play written by an actor, for actors. Ambition never fades, and the characters – a court of hungry young men circling an ageing tyrant – are among the most recognisable that Shakespeare ever created. Power, and those that would have it, never goes out of fashion.

Shakespeare’s revenge-filled play, which sits between his earlier histories (Henry V) and his later tragedies (King Lear) is itself at the turning-point of Shakespeare’s career. By murdering Caesar so early on, the playwright is already learning to surprise his audience. It is a truly fascinating piece of theatre, and Caesar can live in a multitude of guises.

The decision by the Royal Shakespeare Company to go with a classicist interpretation should, in theory, de-clutter Shakespeare’s vision. But by going with the togas-and-sandals that everyone associates with the play means that there is little room for manoeuvre. Like a tailored suit, every line is on display and it has to be perfectly cut.

What director Angus Jackson ends up with is a distancing effect – by keeping to the ancient origins of the play, the action feels at a remove. Julius Caesar is the play of the moment, with several productions expected this year, but this RSC production feels curiously dated. As pundits like to tell us, we are living in extraordinary times, and when a tyrant is more likely to wear a comb-over as a golden wreath, to go retro feels like an opportunity missed.

Shakespeare’s characters are designed to live and breathe – and even up close in the cinema, the main players fail to impress themselves on their audience. Brutus (played by Alex Waldmann) should be bold and daring; here he feels indecisive and small-voiced. He should be master of the sound-bite, but his powers of persuasion are somewhat lacking. It’s no wonder Mark Antony wins over the crowd so quickly – rhetorically, he barely breaks a sweat. As Antony, James Corrigan plays the would-be-king with full-blooded charisma and a vigorous masculinity, even eclipsing the great Caesar himself.

This is a play dominated by male voices, with the volume is turned up loud: respite comes from the sidelines. With a sweetly melodic song, Samuel Littell makes his debut on the RSC stage as Lucius, Brutus’ young servant. His dispatch at the hands of Brutus’ enemies is a moment that audibly shocks the audience. The unflinching way Jackson handles this is reminiscent of Game of Thrones, with its no-holds-barred approach to warfare. You can’t help but wonder why this wasn’t applied to the rest of the play. Even when the action is meant to be spontaneous, the performances are measured and calculated down to the last inch. The exception comes from Tom McCall, who plays Casca with a snide knowingness that reminds us of Shakespeare’s ability to create characters that speak to us, centuries after they were written. Casca is ultimately playing his own game, and his self-interest is instantly recognisable, giving the production glimpses of a contemporary edge it desperately needed.

Julius Caesar is about a state in chaos and decline – and the rulebook is cast aside.

We should feel that danger coursing through the play – that anything, absolutely anything – could happen. Again, the decision to go with the default setting of Ancient Rome means that distance prevents us from making that connection with what’s happening on-stage. Caesar operates in a world beset by rumour and fake news, but the unwillingness of this production to draw parallels with contemporary events seems disingenuous at best. Even though the play is cast in a period setting, Shakespeare wrote Caesar as much about the ancient leader as his own Queen. Whatever backdrop Shakespeare chose, the political landscape was recognisably contemporary. He lived in extraordinary times too – and applied it to his work without reservation.

The production, and its unwillingness to break from tradition, is its undoing. Compare it to the recent NT Live production of Twelfth Night (shown at Plymouth Arts Centre last month), and the difference is quite remarkable. This version of Twelfth Night took risks, not least with its casting. Re-shaping the belligerent man-servant Malvolio as Malvolia (played with aplomb by Tamsin Greig), the production won over audiences with its clear-eyed vision of what a Shakespearean comedy should be.

We have the luxury of comparing the two productions, thanks to the phenomenon of broadcast theatre. A project started by the National Theatre in 2009, the aim was simple: bring the thrill of the theatre to a cinema audience. It was an immediate success, with audiences around the country now having access to the very best in live theatre.

Some of the best nights out I’ve had in the past few years have been thanks to these live theatre screenings. Getting to see the sold-out production of Hamlet starring Benedict Cumberbatch; a whispering King Lear from Derek Jacobi at the Donmar Warehouse and a simmering Dominic West in Les Liaisons Dangereuses. These screenings offer a wealth of possibilities for an audience that might not have the opportunity to go to London to see these performances in-situ. A West End show is no longer the reserve of the privileged; if you can get to a cinema, you can see the show for yourself.

It also means that cultural boundaries are beginning to shift – living in the sticks is no longer the barrier it once was to experiencing great art. The screenings, also featuring art exhibitions, ballet and opera are allowing audiences to make up their own minds about what they like. It’s removing the idea that art and culture are for other people – these productions bring the world in closer, and live theatre is packaged as an exciting, immersive experience for people of all ages and from all backgrounds. You wouldn’t consider a screening of Fast and Furious to be an elitist event, and by showing challenging, complex work on a cinema screen, the element of familiarity helps unlock the production for an audience that may not be used to attending theatre. By taking the fear out of Shakespeare (and Miller, Albee, Ibsen, Chekhov…) the audience gets to engage with a work they might have previously considered too high-brow. But what emerges when you watch these productions is the realisation that there’s no such thing as high-brow, middle-brow or low-brow: a production is either successful or it isn’t. They’re both Shakespeare, but Twelfth Night’s free-wheeling spirit worked where Julius Caesar floundered.

The screenings make critics out of us all, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. An audience should feel confident in having their own opinions about what they’ve just seen, and that confidence only comes from watching theatre and watching it on a regular basis. A well-informed audience then demands excellence, and our theatre industry with its wealth of talent, is only to happy to rise to that challenge. Far from dulling down content, NT Live has offered a programme of theatre and events that provoke and move us. Better-informed audiences mean better art, and by making art more accessible, everybody wins.

Helen is a freelance writer, living and working in Plymouth.

@Scholar1977

Comments

Comments are closed.