By Helen Tope

The story itself is familiar enough. A Scottish lord, Macbeth, yearns for power. On being told by three witches that he will soon be King, the lust for power converts to violent, bloody action. Eliminating rivals, real and imagined, Macbeth’s grip on the crown begins to slip. The reality of what he and his wife have done, takes hold.

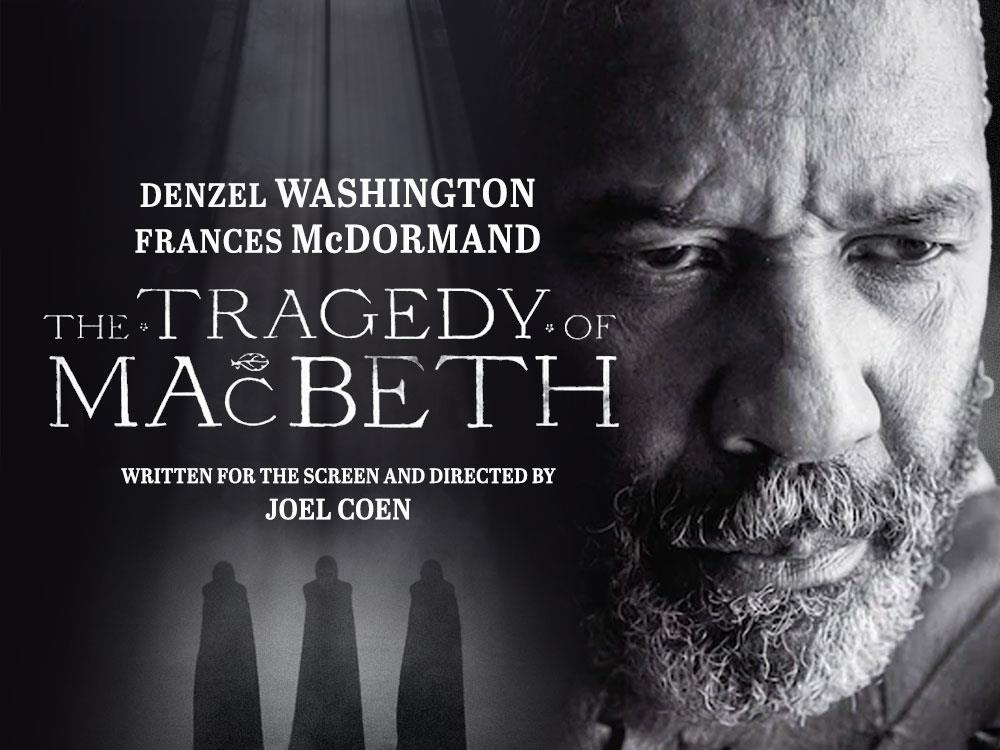

The Tragedy of Macbeth is Shakespeare’s play retold by director Joel Coen. Filmed entirely in black and white, Coen’s cinematic landscape is dour and austere. There are no lush Scottish hills, just peaty bogs, hovels falling into ruins and castles built more to impress than to shelter. Macbeth’s 11th century world is small – suffocatingly so. He lives on a cultural precipice, where modernity is beginning to emerge, but the populace still cling to ancient superstition.

Denzel Washington is cast in the central role (and has received a Best Oscar nomination for his performance) – his Macbeth is in every aspect a warrior: robust, with a keenly physical presence. Paired with Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth, the two actors portray the ultimate power (hungry) couple. Their age is a clever addition to the mix: the sense of desperation, clutching at what they believe to be their last chance, hangs in the air. As they collude to murder the current King (played by Brendan Gleeson) when he visits their castle, the speed at which they formulate a plan makes it clear this has been on their minds for some time.

McDormand, as you might expect, handles Shakespeare with great skill. Out of the pair, she is the one who appears to be most comfortable with the rhythms of the language. She interestingly plays Lady Macbeth as being less at ease with their new-found status as Macbeth takes the crown. While her husband immediately dons the robes and garb, Lady Macbeth realises her role as hostess is not such a great fit.

Their growing ambivalence to their prize is cleverly drip-fed into the screenplay by Coen, but we also realise that as the fallout from the King’s murder brings other players into view, Macbeth’s endeavour must resolve itself, one way or another.

This film is all about the quality of its ensemble, and the casting is superb. Bertie Carvel as the ill-fated Banquo, Alex Hassell’s messenger Ross shifts into the foreground as it becomes clear his true allegiance is to himself. Kathryn Hunter is excellent as the Three Witches – spider-like, she appears to Macbeth as an apparition. Hunter’s other-worldly, unsettling performance is at the heart of Coen’s vision.

The frame of reference for The Tragedy of Macbeth is firmly set in the European cinema tradition, specifically the work of Ingmar Bergman. The soft-wash monochrome, with sharply delineated shadows (cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, also Oscar-nominated) builds tangible, evocative atmosphere. Interiors without decoration, clothes made for utility, only rare moments of luxury. Delbonnel’s camera rests on the bleak, temporary nature of the Macbeths’ new-found success.

This is a very striking, stylised interpretation of Macbeth, but Shakespeare’s play – a tragedy filled with poetry – lends itself to bold takes. The film continually moves between the literal and the abstract, which is entirely appropriate as this is where Macbeth, mired in crisis, finds himself. Sometimes the visual metaphors are over-egged (ravens feature prominently), but the production design marries so well with the intention of the film, it never feels like too much.

There is a restraint at the heart of this project that balances out the louder moments. Washington’s Macbeth is naturally a man of contemplation, which makes his calculated butchery all the more shocking. The sense of alienation that seeps into the film is quite deliberate. Human life may be cheaply regarded here, but Coen reminds us that in this time and place, ambition must be served first, not for an individual’s benefit, but for the continuation of history. Coen’s Tragedy is, for all its visual impact, a work rooted in tradition. We no longer see Macbeth the individual, at the centre of his own story. He is a single piece on a board, part of a much larger game.

Comments

No comment yet.