It’s hard, from our perspective, to imagine a time when Impressionism wasn’t popular. It’s not only popular but ubiquitous. Images of sunlit meadows, leisurely riverbanks and ornate gardens have become artistic shorthand. Even if we think we know nothing about art, identifying a Monet would be easy enough. In their latest film, the Exhibition on Screen team take up the challenge of taking us back to the roots, and the inauspicious beginnings, of Impressionism itself.

Dawn of Impressionism: Paris 1874 starts in a familiar place. We are watching an art auction take place. Impressionist paintings are selling for eye-watering sums. You can have a Degas for 3 million pounds; a Cezanne for 32 million dollars. Ownership of these names comes with a contingent: only the seriously rich need apply. We then take a step back from the moneyed glow. Played over the top of this footage, a voiceover. It is a begging letter from Claude Monet. He finds himself broke once again, and is desperate for money. The documentary defines its territory: the idea of Claude Monet struggling for cash is hard to get your head around.

The inspiration for this film takes shape from the collaborative exhibition staged by the Musee d’Orsay and the National Gallery in Washington. Titled Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment, the exhibition not only explores the origins of the Impressionism movement, but questions how much of our interpretation of it, is truly accurate. In a fascinating coup de theatre, Washington’s National Gallery brings together the works featured in the original Impressionist show, and re-stages it.

The tried-and-tested method of Exhibition On Screen also undergoes an adjustment. As well as the usual blend of detailed camera work and background from the museum’s curators, this documentary gives us the Impressionists; their supporters and critics, in their own words. Dawn of Impressionism assembles the major players and the lesser-known names, which helps to create a sense of their place within the art world. After the deaths of Ingres and Delacroix, the Parisian art scene was stagnant. It needed a new sense of direction. The old school, narrative paintings, often based on biblical subjects, no longer felt fresh or interesting. The art scene was still locked into a Salon system: artists submitted pieces every year to The Salon, hoping to be selected for display. However, the selection committee was mired in an antiquated way of thinking about and looking at art. Some young artists did succeed. Edouard Manet craftily worked the system to agitate the mainstream from within. But the selection process did not often reward experimentation and many early Impressionist works failed to make the cut. The most entertaining part of the documentary is where we are shown paintings that did and didn’t get in. The omissions are honestly jaw-dropping.

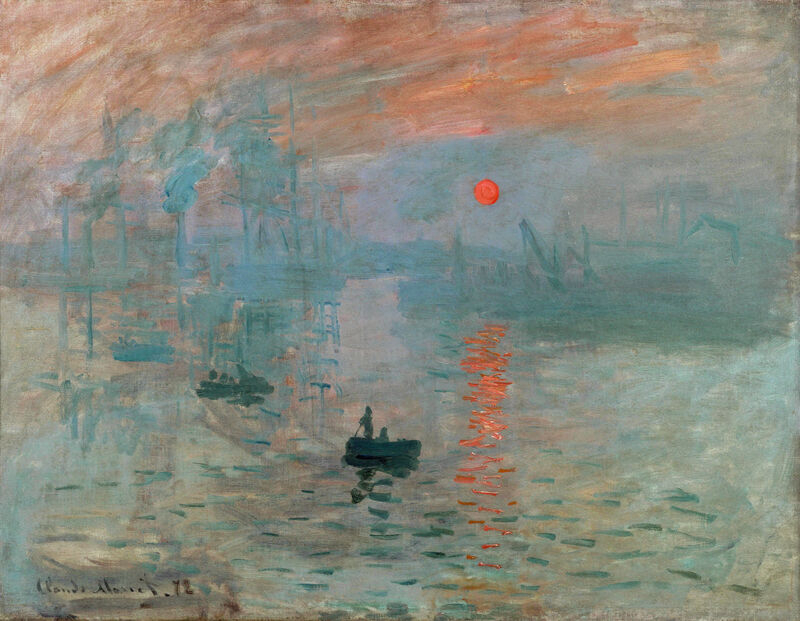

The group of artists that became the Impressionists began to realise that the only way forward was to exhibit independently. Their voice, their rules. The show they staged in the centre of Paris, while inclusive of artists regardless of class and gender, was not a huge popular or critical success. It did not set the art world on fire. Only four paintings sold, including Monet’s Impression, Sunrise. For a modest 1000 francs. A millionaire’s bank account would not have been needed to make a purchase.

Dawn of Impressionism, in its final third, steps away from the artists themselves and back into the 21st century. With the help of the museums’ curators, Exhibition on Screen pieces together what the show tells us about the burgeoning art movement. This becomes the most revelatory section of the film. There are surprises: many artworks featured in the original show would fall outside of what we now define as Impressionist art. What also becomes clear is that the cohesive quality we would expect from a modern show, simply isn’t there. It is literally a collection of work from disparate artists. The definition of what – and wouldn’t be – Impressionism came later. The show also reminds us that the movement was not just about paintings: the original exhibition also featured sculptures, pastels and prints.

While the film plays around with format, most of that risk pays off. However, the middle section of the documentary feels slightly overlong. The obstacles the artists come up against when trying to get their work seen is made pretty clear early on, and it does feel a tad repetitive (although each artist had their own beef with the industry, which we see when Berthe Morisot reinforces just how much harder progression is for a women artist in the 19th century). As a result, the critical exposition in the last part of the film, feels rushed which is a shame as the insights from the curators are really worth paying attention to. Far from being a box-ticking exercise, the exhibition succeeds in making us re-examine what we know about Impressionism. The new angle leans away from the slightly staid reputation the art, ironically, now has, and we go back to a point where Impressionism was considered modern, daring and revolutionary. It revives the artists’ sense of purpose: waking up an art world that had fallen asleep at the wheel; getting out of the studio and into the environment itself. It was not just about moving away from the past, but recording life in the here and now. While its sense of identity emerged later, Impressionism’s faltering, uneasy start was never the point: it was always about autonomy, and that is what they achieved.

Exhibition on Screen: Dawn Of Impressionism Paris 1874 is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema on Thursday 3rd and Saturday 5th April.

Reviewed by Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.