Ieuan Jones reviews David Lynch: The Art Life, which is being shown for just three screenings at Plymouth Arts Centre on 24, 25 and 26 October. Tickets are selling fast, you can purchase yours via our Box Office or on our website.

Earlier on this year, back in May to be precise, something rather miraculous happened. Alright, alright, I’ll tweak that (slightly) – something miraculous happened to those of us fascinated by the work of David Lynch and the return of his genre-bending, form-transforming, reality-melting TV show Twin Peaks.

Those who harboured fears that The Return would be just another run-of-the-mill franchise “reboot” were royally putting their teeth back in within about five minutes flat of the opening credits. Few stayed the course, if the viewing figures released so far are to be believed. This is a shame, since the show was an 18-hour malarial dream of talking trees and radioactive woodsmen falling from the sky. Yet it never felt more daring than in its closing moments, which warped the entire fabric of everything we had seen in a riptide that threatened to drag the entire rest of television away with it. Compared to that, everything else on screen just feels awfully tame and lacking (yes, even Bake Off).

Kyle MacLachlan plays FBI Agent Dale Cooper in Showtime’s Twin Peaks: The Return.

Lynch (with co-creator Mark Frost) had seemingly done the unthinkable. Having already reinvented the wheel back in 1990 on the show’s original run, now, both in their seventies and having been out of the biz for a long old time, they had done it all over again. Twin Peaks: The Return had many, many faces. It was a prolonged meditation on mystery, memory and nostalgia. It provided a kind of psychiatric assessment of America today (hint: the results are not great). Some art bods pointed out that The Return is an example of Lynch’s “Late Style.” This (it says here) is the point at the end of an artist’s career where they have finally achieved full command over their idiom, yet they choose to alienate themselves from it rather than reinforce it. If this is the case, and if we are truly at the endpoint of Lynch’s art, then what better time than now to go back to the drawing board?

David Lynch: The Art Life concentrates on the man and his studio, rather than the man behind the lens. Specifically, it is a portrait of the artist as a young man, from his formative, boyhood years right through to a lightbulb moment where he sensed that the pictures he was painting could be moving. So we get lots of shots of Lynch smearing and squelching his way around canvasses intercut with lengthy monologues.

It is a film of impressive depth, considering its relatively small scope. Lynch isn’t the most forthcoming person in interviews – you usually have to scrape and scour for much insight into the man rather than the myth. Speaking into his immaculate fifties microphone in what looks like some kind of red confessional, he gives much away here with impressive ease. He only appears to stumble once, when talking about his rebellious teenage years and the hurt he feels this brought to his family. But even then he makes clear the huge affection he has for his parents and the Eisenhower-era America in which he grew up – variously moving around Montana, Idaho, Washington, North Carolina and Virginia. He makes a chance encounter that convinces him that he could live an entire life, smoking cigarettes in his studio and living what he would come to term the “art life”.

“He only appears to stumble once, when talking about his rebellious teenage years and the hurt he feels this brought to his family”

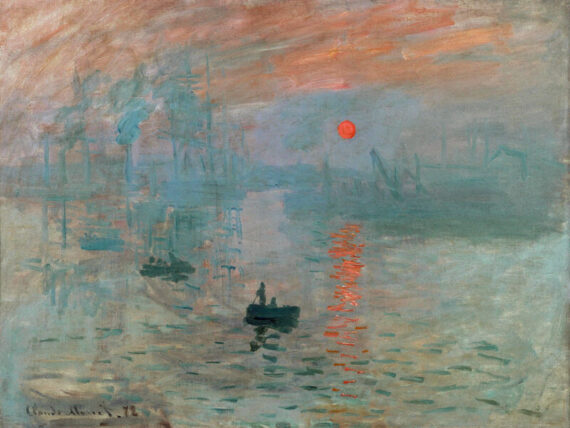

Lynch’s art is reflective of a man apparently stripped of innocence – in fact he even puts it down to a single moment. One night, as a young boy in his idyllic neighbourhood he saw a naked and emaciated woman stumbling in the dark – an impressive image that made its way into his keystone film, Blue Velvet. His paintings are mainly bleak images, all blacks and foggy greys, full of dismemberment and confusion. They are also heavily dependent on language – more or less every painting we are shown contains writing in one way or another. “Oh, my thoughts are so mixed up and funny!“, laughs a man seemingly drowning in clouds of ink. “I fight with myself,” says another, whose head is pulling itself in two. Perhaps it was only natural that he would then go on to make talking pictures.

But there is something else going on here, something I admit I had not really appreciated before with Lynch in his filmmaking, but is maybe key to unlocking a very important part of his work – vulnerability. By allowing us in to investigate those years of his life to which he had previously been tight-lipped, this film allows us at last the chance to see the fragile man standing behind it all.

David Lynch: The Art Life contains further important revelations about America’s greatest living artist and should be a set text for those with even a passing interest in him and his work.

Ieuan Jones is a regular contributor to the Plymouth Arts Centre blog, living and working in Plymouth.

Comments

Comments are closed.