Aged 31, Londoner Daphne is single, living alone and working in a restaurant. Placated by alcohol and casual drug-taking, she is skimming through life. Daphne may exude a cooler-than-thou attitude, but behind the persona, is a girl who wants more.

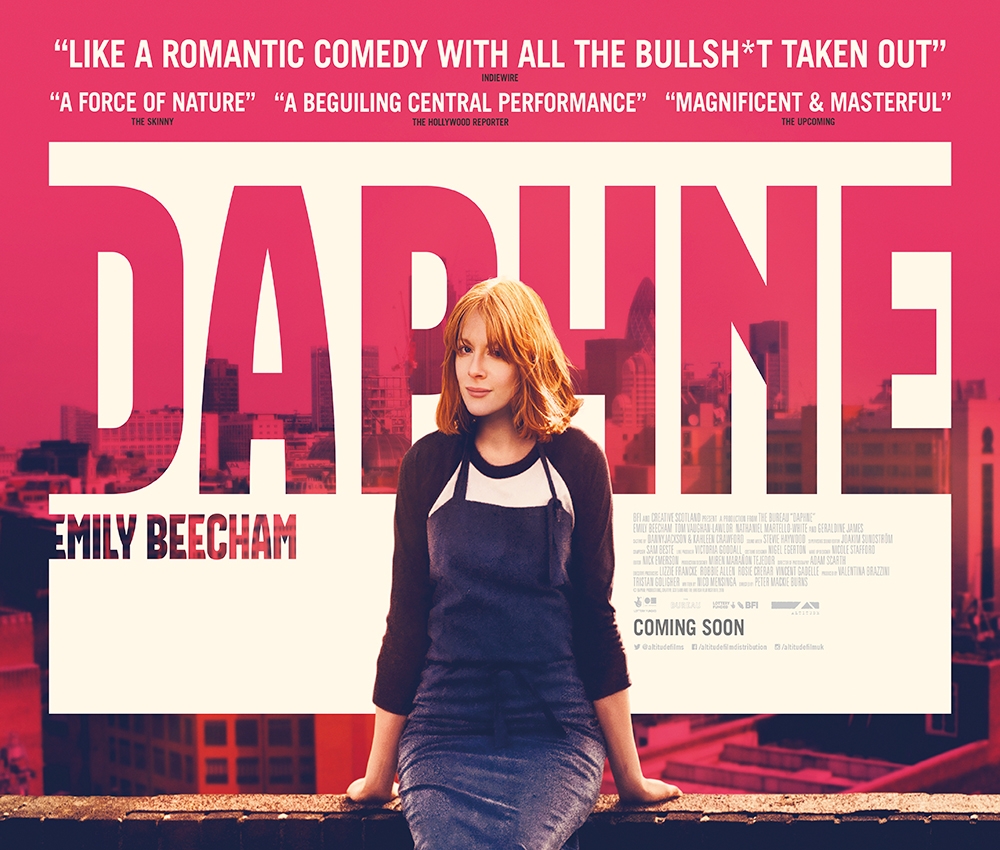

Daphne is showing in the cinema from 24 – 30 November. Helen Tope Reviews:

The tedium of Daphne’s life is broken when she walks into a corner shop to buy cigarettes. As she stands at the counter, a man on a motorbike pulls up outside. With the engine still running, he bursts into the shop, demanding money from the owner, and becomes violent.

After witnessing this horrific crime, Daphne receives a message from Victim Support, offering her counselling. She ignores the message and goes to work instead.

In trying to pick up where she left off, Daphne (played by Emily Beecham) struggles to cope with the pretence. She begins to unravel, her work begins to deteriorate, and the few relationships she maintains, are kept at arm’s length. Drugs and alcohol become a more prominent feature, as Daphne’s behaviour becomes increasingly erratic.

Daphne’s attempt to self-medicate fails miserably. With little left to lose, Daphne takes up the offer of counselling. We learn that she doesn’t even know if the shop-keeper survived the stabbing. The counsellor advises her to find out.

A skillful piece of film-making, Daphne’s power lies in the building up of small moments; the asides, the glances, the near-misses. The way the film pieces the narrative together is not only confident, but assured. In a scene with her therapist, Daphne is told that emotions needn’t be ‘operatic’ to be important, and it is this credo that defines the film.

Director Peter Mackie Burns creates Daphne’s inner world with detail. The stern, unyielding row of spikes decorating the town-house Daphne leaves after an encounter; the aerial shots, showing Daphne weaving in and out of traffic. Sound plays a huge role in this film, with the revving of a motorbike dotted throughout, like a haunting refrain. It, like the circle of events that crowd Daphne’s mind, is never too far away.

The same device is employed with the dialogue. After the incident, Daphne’s patter turns brittle and staccato. The word ‘stab’ appears and reappears, leaping out of her sentences, a red flag, waving for help.

As a study of trauma, and the damage it can do, Daphne excels. The incident seeps into Daphne’s psyche, layer by layer, like an untreated burn. Left alone, it just goes deeper and deeper.

For a film that sidesteps the bells and whistles, Daphne is psychologically astute and profound. But where the film branches off in its own direction, is in its refusal to play big with those emotions. Everything is understated; the devastation Daphne feels is all too clear, but not for show. Her upended life is not entertainment; the film in parts almost feels like a documentary. We are watching the healing of a young woman, but nothing is guaranteed: it is a delicate process. Her unsteady progress makes us root for Daphne all the more, giving the final scenes an extraordinary poignancy.

Every aspect of this film is beautifully judged; the dialogue, the pacing. Nothing is ever leaned on too heavily. The director applies the lightest touch, creating a film of real subtlety and sophistication. But more than that, Daphne makes us care about the fate of its characters.

Daphne separates itself from the big-hitters by refusing to press our buttons. It allows us to become emotionally invested, but does not insist upon it. The exploration of trauma is not a new subject, but in the treatment of how Daphne’s life implodes, this film makes you question why we need scenes of explosive emotion, when this approach is so much more effective.

With Oscar nominations coming out in January, Daphne raises interesting questions about what constitutes an award-winner. Oscar-worthy films have, by tradition, been big hitters. Big emotions and big performances for the big screen. Even with low-key films, such as last year’s Manchester By The Sea, we still have moments of breakdown; emotions writ large.

In Daphne, not a tear is shed by its heroine, but Beecham still delivers a performance of great depth and complexity. Daphne may be about the avoidance of emotion, but it is seen and felt in every moment. It doesn’t need to coax empathy from its audience, because it recognises that it is already there.

To look beyond the alienation of modern life and see something universal takes courage. It is easy to be cynical, but as Daphne learns, being vulnerable yields its own power. A brave film in every respect, Daphne offers a new way of telling an old story, and that achievement deserves to be recognised.

Comments

Comments are closed.