Earlier this month, I was invited to attend a PAC Home Talk by conceptual artist, Peter Liversidge. Born in 1973, Peter’s work has appeared in exhibitions both at home and abroad.

His career path began studying Fine Art at the University of Plymouth, as he began to notice that his peers were becoming increasingly concerned with finding and developing their ‘signature style’. Peter rebelled against this idea of producing repetitive, self-definable art – choosing instead to work in a huge variety of mediums including performance, photography, drawing and sculpture. The result is a career that gleefully defies expectation.

Peter’s talk outlined his projects to date, the collaborations and exhibitions that have appeared around the world, whilst sharing a slideshow of images detailing his personal influences.

Peter Liversidge is the kind of artist only Britain could produce. Producing work with a Milligan-esque, absurdist humour, his range of influence is vast. A self-confessed music obsessive, Liversidge also takes inspiration from conceptual artists such as On Kawara and Keith Arnatt, along with the Keaton and Chaplin physical comedy that forms the basis of work from Fischli and Weiss.

Peter’s works all start the same way – as a proposal, typed up on his typewriter, an Olivetti Lettera 35. The typewriter is a deliberate choice, as any spelling mistakes or errors cannot be erased and become part of the piece. The proposals can describe ideas from practical to purely hypothetical, and are contained within a self-imposed timeline or are related to forthcoming projects and exhibitions.

Peter discussed his piece ’64 Proposals’ (displayed in London’s Whitechapel Gallery), where the typed-up proposals are presented as the artwork; a beginning and end in themselves with the viewer taking the final step in the process by reading and interpreting the proposals. These proposals may only exist physically on paper, but come alive in the viewer’s imagination. The project only becomes whole when in the presence of those who visit the gallery. Liversidge in this piece extended the role of art-maker to the audience; an invitation to create.

What is clear in looking at Liversidge’s pieces is that he puts the viewer at the centre of his work. While some of Peter’s proposals are destined to stay on the page (including his ongoing proposal series with books containing hundreds of ideas), some of Peter’s proposals are fully realised and made into projects for exhibition.

Peter produces artwork using everyday objects: either repurposing them to create new works of art, or re-fashioning a pre-existing object for use in a new, unfamiliar context. In a tradition dating back to Marcel Duchamp, Peter discussed his project ‘Masks’, which began when he found a coffee-holder in his studio and painted it black. The holes created a tribal mask effect with the paint fading and streaking to create a black / bronze patina. The throw-away object then became a piece of art, and our perceptions of it therefore change. Liversidge is very much driven by creativity for its own sake, believing that art works best outside the exacting parameters of ‘fine art’.

His repurposing of the everyday world comes to life in his exploration of Mail Art (an artistic movement based on the sending of small-scale pieces through the postal service). Peter’s recent work ‘New York Postal Shelf’ bridged performance art with curatorial practice as Liversidge posted items from London to the Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. The gallery purposely-built a shelf for the items to sit on, and responsibility of where to place them was given to postal worker, Dana, who regularly delivered post to the gallery. The piece then circumnavigated usual curatorial practice, as Dana’s ad-hoc decisions on how to display the items gave the work potential for endless reinterpretation.

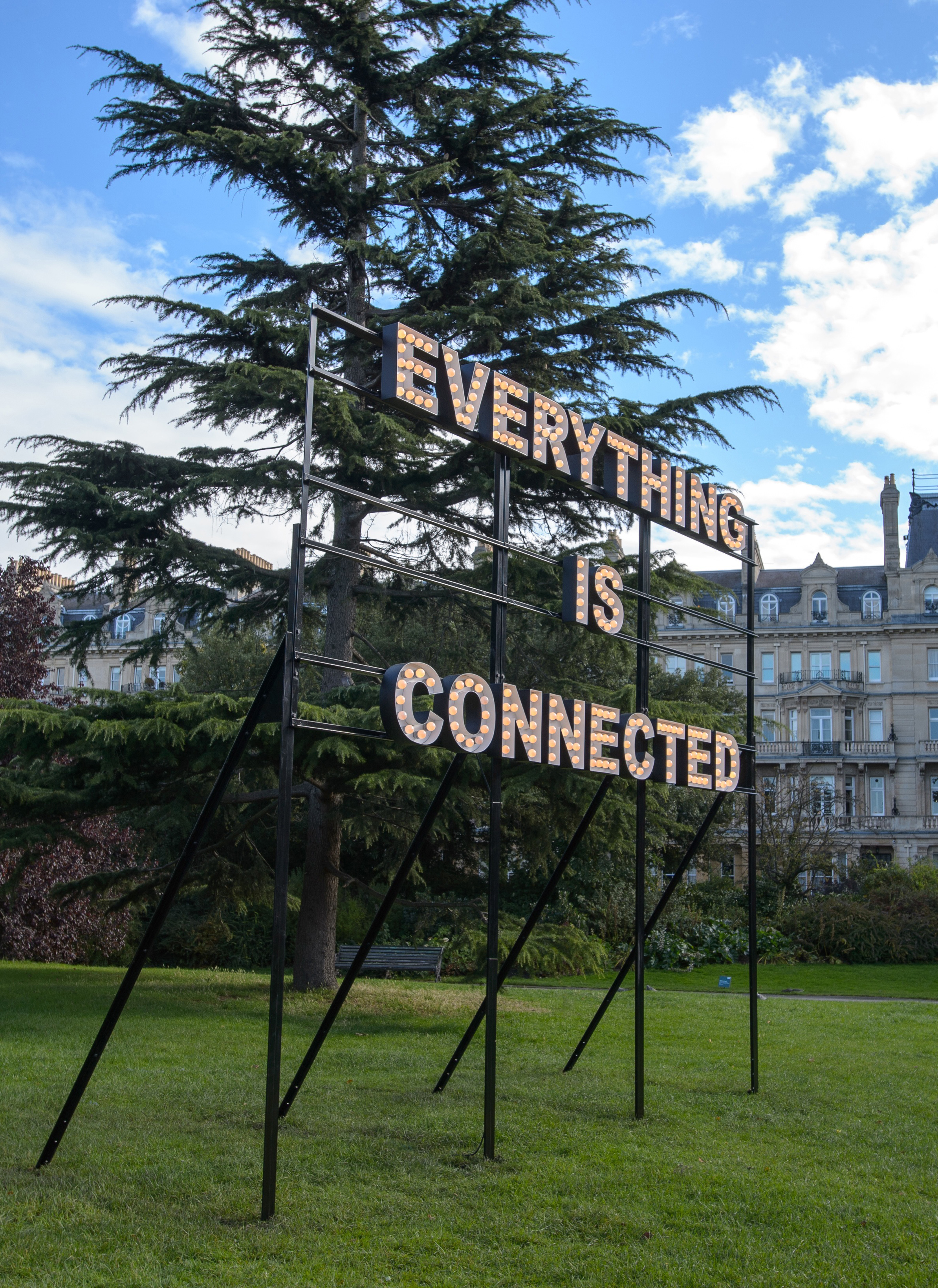

I think what Liversidge does so eloquently is to celebrate the connectedness of experience itself. The moments of potential particularly interest him; which is why so many of his works rely on the presence of an audience. The energy between an artwork, the artist and their audience rises exponentially when barriers are removed. By bringing the art up close and personal, the invitation is there – whether you participate and unlock the work’s potential (or not).

Peter may stress that he has no signature style, but his signature runs through every work, every proposal. Inclusion – it’s the one idea that moulds Peter’s body of work together, regardless of method or material.

In an art world where curators themselves are becoming the stars (think of the Serpentine Gallery and you immediately think of its superstar curator, Hans Ulrich Obrist), Peter Liversidge presents art where a point of view is deliberately removed. The one thing his projects all have in common is that there is no leading narrative, no-one nudging you in the ‘right’ direction. He is an artist that avoids easy definition, or indeed much definition beyond the broad spectrum of ‘conceptual artist’. That is the very point for Liversidge – the concept is all.

He is an ideas man, through and through – and that is what makes him so engaging. He presents ideas as open-ended: they can remain as they begin, just a notion – or the viewer can take them further, becoming creators themselves by providing their own interpretation of the work. In handing over that right of completion to the audience, Peter makes a very powerful statement on ‘ownership’ and a modern art world where commerce and politics are so closely linked.

The accessibility of his projects has made Liversidge a very timely success story. His emphasis on the act of art-creation itself, encouraging the viewer to become an active participant is gaining popularity, as we saw with the recent Turner Prize win for architectural collective. Assemble. Art is not content to remain within the confines of the gallery space anymore, but heading out into the community. There is a perception – rightly or wrongly – that contemporary art marginalises, and Liversidge is ahead of the curve, by proposing art that puts the viewer at the heart of the matter, giving them the option to create moments or simply to walk away. It is a dramatic shift in power; a bold attempt to create lasting connections between those who view contemporary art and those who make it. If the impact of Liversidge’s work is any indication, the possibilities are endless.

Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.