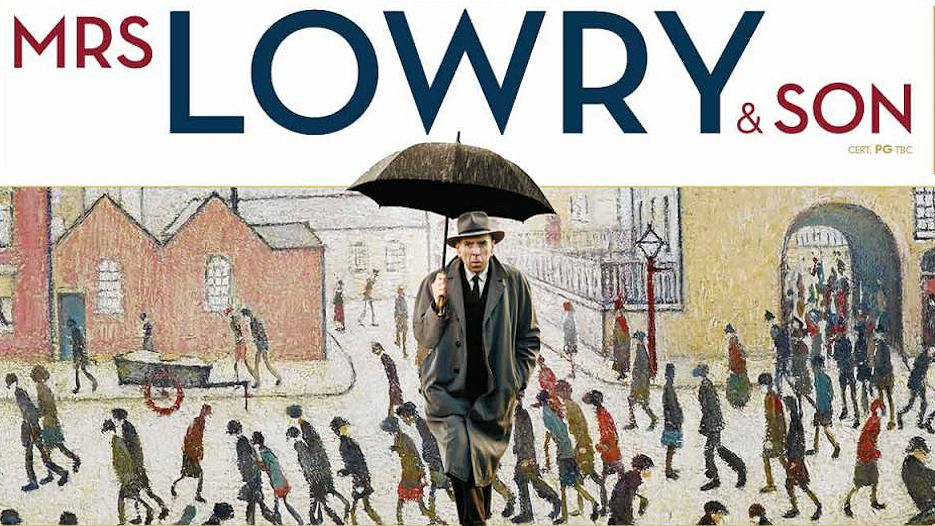

Helen Tope reviews Mrs Lowry and Son, showing in our cinema until Thursday 3 October.

Filmed with a lightness of touch, Mrs Lowry and Son is a delicate portrait of a complex and deeply troubled relationship. LS Lowry, whose works include Going to the March and Coming from the Mill, lived with his mother Elizabeth until her death in 1939.

We join them five years earlier. Living in a terraced house in Pendlebury, tensions emerge right from the start. Mrs Lowry identifies herself as firmly middle-class. We learn that the Lowrys started life as a family in a plush suburb of Manchester. Living beyond their means, and debts piling up, the family had to downscale and flee the creditors. Blaming Lowry’s father for their disgrace, Mrs Lowry clings to the past – the film hints at her musical talent – a talent left unfulfilled.

With Lowry’s father now deceased, it falls to the son to care for his increasingly bedridden mother. As Mrs Lowry, Vanessa Redgrave plays a woman not just weighed down by disappointment, she is furious at her lot. The rage turns towards LS Lowry himself; at this point, working as a clerk and retiring to the attic at night to paint.

So far, Lowry’s potential has been limited. A local critic eviscerates Lowry’s work, much to Elizabeth’s embarrassment. But there is hope. Lowry has received a letter from an art dealer in London. He has seen some of Lowry’s work, and would like to see more, possibly to stage an exhibition. It is the breakthrough Lowry has been waiting for. All that is left is to tell his mother.

As a psychological study, Mrs Lowry and Son excels. The dynamic between the artist and his mother is filled with pain: left unresolved and inarticulate, the relationship begins to fall apart. Mrs Lowry, despite her artistic sensibility, cannot see the artist in her son. His work, to her, is crude, ugly and uninspiring. Mrs Lowry cannot see that the industrial landscapes her son creates are bold and subversive.

In examining Lowry’s relationship with his mother, director Adrian Noble also illustrates how the balance of artistic reputation can tip this way or that. Lowry’s now-famous stick figures – as much the interpretation of modern man as Magritte or Giacometti – were derided by early critics. In scenes recreating Lowry’s brushstrokes, it is obvious that the figures ‘a child could draw’ are starkly beautiful and skilfully produced. The marks are not by chance, but appear by means of precision and wit.

It is Lowry’s ability to see the beauty in the ordinary that speaks to us now. The class lines that dictated the Lowrys’ downfall are not as sharply drawn as they once were, but in expressing the individuality of working class people, Lowry was years ahead of his time. It is little wonder that his mother preferred Sailing Boats, 1930.

Timothy Spall also has previous form in playing a British great. As the artist in Mike Leigh’s Mr Turner, Spall went the extra mile to give his performance authenticity, taking up lessons in drawing and painting. Spall’s performance here, to suit the film, is less technical, with emphasis on the emotional drive Lowry needed to produce his work. Buttoned-down and eager for praise, Lowry keeps the note from the art dealer, stored safely in his suit pocket. During an argument, he finally hands the note to his mother to read. She tears it into pieces. This is the kinetic jump Lowry needs to release his fury.

Mrs Lowry’s inability to see talent in her son goes far deeper than artistic difference; a nastier vein of sourness and regret is at work here. Not only has he failed to measure up to her image of success, she reveals that she never wanted him in the first place. In a fit of rage, Lowry gathers up his paintings, and threatens to torch them in the garden. His mother, screaming at him from her bedroom, urges him to do it.

Where Turner, unencumbered, restless – sought inspiration from every corner, Lowry finds it much closer to home. Lowry’s Coming from the Mill – nearly sold to his neighbour for £25 – uses scale to demonstrate enormity and intimacy all at once. Noble uses the same approach in his film-making: the lion’s share of the action takes place in Elizabeth’s bedroom. Cramped, confined and packed with antiques of dubious origin, the effect is stifling. The world, when viewed from this perspective, feels very small indeed. As Spall takes to the street in rare moments of escape, we can feel the air – riddled with pollutants from factory chimneys – filling our lungs. It may be grimy and mucky, but to Lowry, it’s freedom. In playing the artist, Timothy Spall brilliantly depicts the inner life of a man struggling for air.

The use of colour in Lowry’s work – neutrals with splashes of boldness – is referenced throughout. The film cleverly balances the flamboyance of Elizabeth’s dusky eiderdown and the rigid palette of browns and blacks that Lowry uses for himself. The absence of colour, normally a signifier of blandness and anonymity, is here a framework on which Lowry hangs his ideas. Individualism, character – everything in Lowry goes deeper than first appearances might suggest.

As the artist’s mother, Vanessa Redgrave gives voice to a maternal presence that’s anything but cosy. Arch, abrasive and laced with self-pity, Elizabeth Lowry’s sense of disappointment for herself seeps over into the next generation. Urging Lowry to give up on his art, to seek a life more ordinary, she is the grist Lowry has to work against. Indeed, the film questions whether Lowry’s ambition would have been burned quite so fierce, had he received nothing but love and encouragement. His striving to paint for his mother’s approval inured him to the harshest criticism. He’d already heard far worse at home.

What the film celebrates is the persistence of a single voice. Lowry’s vision was unique, and proudly so. He stepped away from traditional subjects, and went straight to the industrial heartland. As with every radical artist, time softens the edges and Lowry’s style has since been co-opted into a nostalgia that Lowry himself would not recognise. What Mrs Lowry and Son does it to remind us of just how radical Lowry’s approach really was. The quality of his work, subject and style, wasn’t widely appreciated until the 1960’s – a decade where working class talent was finally able to make its presence felt.

In a nicely-judged coda, we see Spall, still dressed as the artist, walking around The Lowry gallery in Salford Quays. We pause to consider the landscapes and portraits. Spall turns and smiles at the camera – today these paintings are worth millions, and Lowry’s reputation is assured. The balance has tipped, and it has fallen in Lowry’s favour.

Helen Tope

Comments

Comments are closed.